Abstract

Background

Antimicrobial resistance has decreased eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori infection worldwide. A sequential treatment schedule has been reported to be effective, but studies published to date were performed in Italy. We undertook this study to determine whether these results could be replicated in India.

Methods

A randomized, open-labeled, prospective controlled trial comparing sequential vs. standard triple-drug therapy was carried out at Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai. Two hundred and thirty-one patients with dyspepsia were randomized to a 10-day sequential regimen (40 mg of pantoprazole, 1 g of amoxicillin, each administered twice daily for the first 5 days, followed by 40 mg of pantoprazole, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 500 mg of tinidazole, each administered twice daily for the remaining 5 days) or to standard 14-day therapy (40 mg of pantoprazole, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 1 g of amoxicillin, each administered twice daily).

Results

The eradication rate achieved with the sequential regimen was significantly greater than that obtained with the triple therapy. Per-protocol eradication rate of sequential therapy was 92.4 % (95 % CI 85.8–96.1 %) vs. 81.8 % (95 % CI 73.9–87.8 %) (p = 0.027) for standard drug therapy. Intention-to-treat eradication rates were 88.2 % (95 % CI 80.9–93.0 %) vs. 79.1 % (95 % CI 71.1–85.4 %), p = 0.029, respectively. The incidence of major and minor side effects between therapy groups was not significantly different (14.6 % in the triple therapy group vs. 23.5 % in sequential group, p = 0.12). Follow up was incomplete in 3.3 % and 4.7 % patients in standard and sequential therapy groups, respectively. Sequential therapy includes one additional antibiotic (tinidazole) that is not contained in standard therapy.

Conclusions

Sequential therapy was significantly better than standard therapy for eradicating H. pylori infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection is very common worldwide and is responsible for several diseases [1]. The Maastricht consensus group recommends eradication of H. pylori in many clinical situations [2]. Many treatment protocols have been trialed for the eradication of H. pylori. Triple-drug therapy with clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and proton-pump inhibitors is the most frequently used. Since eradication rates are often insufficient with triple-drug therapy [3], alternative treatment protocols have been proposed and trialed on treatment-naive patients. Clarithromycin resistance was the reason for failure in one third of the cases in which eradication was not achieved using the standard triple treatment [4]. Very successful eradication rates in naive patients and resistant cases have been reported using sequential treatment.

The Maastricht III guidelines recommended treatment of the infection in peptic ulcer disease, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, atrophic gastritis, postresection of gastric cancer, and first-degree relatives of gastric cancer [5]. In primary care, a “test-and-treat” strategy for patients with dyspepsia has been advocated [6].

The present study compared the efficacy of a sequential drug regimen with that of standard triple therapy in the eradication of H. pylori infection.

Methods

This was a prospective, open label controlled clinical trial with two groups. At baseline, patients were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion criteria and provided written informed consent. Patients were then randomly assigned to a treatment group and had follow up evaluations to assess the eradication rate of H. pylori infection, treatment adherence, and side effects. The institutional ethics committee approved the study. All patients with eradication failure were offered a rescue therapy.

Setting and participants

Between July 2011 and June 2012, consecutive patients with dyspepsia and H. pylori infection, of age greater than 20 years, were enrolled. H. pylori infection was diagnosed by gastroscopy and RUT or biopsy. Patients with history of gastrectomy, gastric malignancy, previous allergic reaction to antibiotics (amoxicillin, clarithromycin, tinidazole) and proton-pump inhibitors (pantoprazole); pregnant or lactating women; patients with severe concurrent disease, such as cirrhosis, or chronic kidney disease; patients who could not give informed consent; and patients taking NSAIDs and antibiotic treatment were all excluded.

Randomization and interventions

Patient allocation was determined through a computer-generated randomization chart stratified according to center. Randomization used a block design with a block size of four. Patients were randomly allocated to receive a 10-day sequential regimen (40 mg of pantoprazole, 1 g of amoxicillin, each administered twice daily for the first 5 days, followed by 40 mg of pantoprazole, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 500 mg of tinidazole, each administered twice daily for the remaining 5 days) or standard therapy (40 mg of pantoprazole, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 1 g of amoxicillin, each administered twice daily for 14 days). Patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer were continued on pantoprazole for 1 month following completion of eradication regime.

Measurements and outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was eradication of H. pylori infection. Secondary outcomes were adherence to therapy and the frequency of self-reported side effects.

Endoscopy

All patients with dyspeptic symptoms had upper endoscopy and biopsy. Rapid urease test (RUT) (Pylodry™, Halifax Research Laboratory, Kolkata, India) was done. Two specimens were taken from the antrum, and two were taken from the corpus for histologic evaluation. The specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stains, and gastritis was scored by using the updated Sydney system. The specimen for RUT was taken from the antrum at baseline, and at follow up endoscopy, from the antrum as well as the corpus. The distribution of H. pylori becomes patchy following treatment, so biopsy needs to be taken from the antrum as well as the corpus. RUT was read at 3 and 24 h postbiopsy. Patients were classified as having H. pylori infection if either RUT or histology was positive for the same.

Treatment adherence and side effects

Patients were asked to return at the completion of therapy to assess adherence to therapy and side effects. We first asked open-ended questions on side effects and then asked specific questions on anticipated side effects. Adherence was defined as consumption of more than 90 % of the prescribed drugs and was determined by pill counts. Side effect assessment was done by using the temporal relationship of the symptom to the start of therapy. Any symptom that began after treatment was assumed to be related to the drug.

Confirmation of eradication

The RUT was repeated 4 weeks after treatment was stopped. The infection was considered to have been successfully eradicated if the RUT was negative.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0. We calculated the differences between the proportion of eradicated infections for the two treatments by using Fisher exact test, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

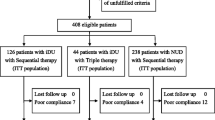

A total of 231 patients were enrolled. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through the trial. Their clinical and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Seventeen patients were excluded from the study. Infection was eradicated in 98 of the 106 patients who returned for follow up testing in the patients treated with sequential regimen, while 95 of 116 patients treated with triple therapy had eradication (Table 2). The eradication rates achieved with the sequential treatment were 92.4 % by per-protocol analysis and 88.2 % in the intention-to-treat analysis. Over 95 % of the patients reported 100 % adherence to the treatment, and none discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Side effects reported in the triple therapy group in 14.6 % of the patients included nausea, pain in the abdomen, and diarrhea while 23.5 % of the patients in the sequential therapy had side effects (patients reported metallic taste, diarrhea, and nausea). All these disappeared by the end of treatment. At follow up endoscopy, in the triple therapy group, four of five patients with gastric ulcer and all six patients with duodenal ulcer had complete healing whereas all patients except one with large gastric ulcer (3 cm × 3 cm) had complete healing in the sequential therapy group.

Discussion

In order to bring the eradication rate closer to 100 %, more effective first-line treatment regimens for H. pylori are required. Eradication rate for standard triple therapy falls well short of this target, even when it is administered for 14 days. Our study confirms earlier results suggesting that sequential therapy has high efficacy and is a suitable alternative to standard triple therapy. Ninety-five of 120 patients in the triple therapy group and 98 of 111 in the sequential treatment group had eradication of infection, with equivalent side effects in the two groups.

The cure rates of sequential drug therapy found in our study are lower than those found in previous studies that showed eradication rates of 98 % per-protocol [7, 8]. In a prospective, randomized controlled trial including over a thousand patients, Zullo et al. found eradication rates for the sequential regimen of 92 % by intention to treat and 95 % per-protocol [9]. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Vaira et al. found corresponding rates of 89 % and 93 % [10]. Finally, in a recent systematic review including over 1,800 patients, Zullo et al. assessed the current evidence on sequential treatment. Pooled data analysis showed an excellent intention-to-treat cure rate of 93.5 % [11]. Chaudhuri et al. showed that lower eradication rates of treatment regime may be related to subtle changes in bacterial genotype [12], but genotype analysis is not widely available at present. Sequential therapy has been shown to achieve better eradication rates than 7-day triple therapy. In a study by Valooran et al., following simple closure of a perforated duodenal ulcer, the eradication rate of H. pylori with 10 days of sequential treatment was 87.09 % compared to 81.25 % with triple therapy for 10 days (p = 0.732) [13]. Other randomized trials have reported better results with sequential therapy than with longer triple therapy schedules [14], and similar results have been obtained in comparative studies in children and in the elderly [15]. An advantage of sequential treatment is that it is not affected by the risk factors associated with triple therapy failure, such as clarithromycin resistance, the absence of the CagA gene, smoking habit, or the presence of nonulcer dyspepsia. Hassan et al. found that sequential therapy maintained a cure rate of 93 % even after halving the dose of clarithromycin. Sequential treatment seems to have at least the same efficacy as quadruple therapy or a 14-day triple therapy. A study by Amarapurkar et al. showed that quadruple therapy for initial treatment of H. pylori infection did not offer any advantage over standard triple therapy [16]. Kumar et al. found similar eradication rates with triple and quadruple treatment regimes [17]. In addition, sequential treatment showed neither the high rate of side effects and low compliance of quadruple therapy, nor the reduced efficacy of triple therapy, in clarithromycin-resistant strains. Data available in our country on antibiotic resistance are scant. A multicenter study on in vitro susceptibility of H. pylori found 77.9 % resistance to metronidazole, 44.7 % to clarithromycin, and 32.8 % to amoxicillin [18]. A study from Kolkata reported that 85 % of strains were resistant to metronidazole and 7.5 % to tetracycline [19]. The high rate of antibiotic resistance, indiscriminate use of antibiotics, and the suboptimal dose of antibiotics in fixed-dose combinations used for H. pylori eradication have been used as arguments against indiscriminate eradication therapy [20]. A highly effective first-line therapy should improve the efficacy of treatment and reduce therapeutic failure, eventually leading to increased cost-effectiveness.

While H. pylori eradication should be attempted in patients with proven peptic ulcer disease, it has been calculated that its empiric use in nonulcer dyspepsia will cure symptoms only in 1 out of every 18 treated patients [21]. In uninvestigated dyspepsia, the “test-and-treat” strategy has been advocated when the infection rate in the general population is greater than 10 %, but this increases the cost in the primary care setting [22].

Ideally confirmation of eradication following treatment should be done using the urea breath test which assesses the distribution of H. pylori in the entire stomach. In this study, RUT was used to confirm eradication at follow up endoscopy because of nonavailability of urea breath test at the institute. The distribution of H. pylori is patchy posttreatment, so the two biopsies were taken from the antrum as well as the corpus. In the majority of India trials on eradication, RUT was used to assess the clearance of the infection [23]. In a prospective study from North India that used urea breath test, urease test, and histology to confirm eradication, only 46 % of patients had eradication of infection [24]. In a study by Bapat et al., reinfection following eradication was reported as 2.4 % while another study from India reported a reinfection rate of 60 % [25, 26]. The reinfection rate in the present study needs to be assessed at long-term follow up. The eradication rate with triple therapy in our study needs confirmation by long-term follow up. We conclude that sequential treatment may be a valid alternative to the current first-line treatment for the eradication of H. pylori.

References

Megraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993;22:73–88.

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, et al. European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–64.

Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Schneider-Brachert W, et al. A prospective, randomized study of quadruple therapy and high dose dual therapy for treatment of Helicobacter pylori resistant to both metronidazole and clarithromycin. Helicobacter. 2003;8:310–9.

Vakil N, Lanza F, Schwartz H, et al. Seven-day therapy for Helicobacter pylori in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:99–107.

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III consensus report. Gut. 2007;56:772–81.

Chiba N, Van Zanten SJ, Sinclair P, Ferguson RA, Escobedo S, Grace E. Treating Helicobacter pylori infection in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian adult dyspepsia empiric treatment-Helicobacter pylori positive (CADET-Hp) randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324:1012–6.

Zullo A, Rinaldi V, Winn S, et al. A new highly effective short-term therapy schedule for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:715–8.

De Francesco V, Zullo A, Hassan C, et al. Two new treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomised study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:676–9.

Zullo A, Vaira D, Vakil N, et al. High eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori with a new sequential treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:719–26.

Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556–63.

Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353–7.

Chaudhuri S, Chowdhury A, Datta S, et al. Anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy in India: differences in eradication efficiency associated with particular alleles of vacuolating cytotoxin (vacA) gene. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:190–5.

Valooran GJ, Kate V, Jagdish S, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple drug therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer following simple closure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1045–50.

Francavilla R, Lionetti E, Castellaneta SP, et al. Improved efficacy of 10-day sequential treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1414–9.

Hassan C, De Francesco V, Zullo A, et al. Sequential treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication in duodenal ulcer patients: improving the cost of pharmacotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:641–6.

Amarapurkar D, Makesar M, Amarapurkar A, Das HS. Helicobacter pylori eradication: efficacy of conventional therapy in India. Trop Doct. 2004;34:101–2.

Kumar D, Ahuja V, Dhar A, et al. Randomized trial of a quadruple-drug regimen and a triple-drug regimen for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: long-term follow-up study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:191–4.

Thyagarajan SP, Ray P, Das BK, et al. Geographical difference in antimicrobial resistance pattern of Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates from Indian patients: multicentric study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:1373–8.

Datta S, Chattopadhyay S, Patra R, et al. Most Helicobacter pylori strains of Kolkata in India are resistant to metronidazole but susceptible to other drugs commonly used for eradication and ulcer therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:51–7.

Ramakrishna BS. Helicobacter pylori infection in India: the case against eradication. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:25–8.

Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1, CD002096.

Talley NJ, Vakil N. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2324–37.

Bhasin DK, Sharma BC, Ray P, Pathak CM, Singh K. Comparison of seven and fourteen days of lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a report from India. Helicobacter. 2000;5:84–7.

Bhatia V, Ahuja V, Das B, Bal C, Sharma MP. Use of imidazole-based eradication regimens for Helicobacter pylori should be abandoned in North India regardless of in vitro antibiotic sensitivity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:619–25.

Bapat MR, Abraham P, Bhandarkar PV, Phadke AY, Joshi AS. Acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection and reinfection after its eradication are uncommon in Indian adults. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:172–4.

Nanivadekar SA, Sawant PD, Patel HD, Shroff CP, Popat UR, Bhatt PP. Association or peptic ulcer with Helicobacter pylori and the recurrence rate. A three year follow up study. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38 Suppl 1:703–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nasa, M., Choksey, A., Phadke, A. et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomized study. Indian J Gastroenterol 32, 392–396 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-013-0357-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-013-0357-7