Abstract

Purpose

In patients with perianal fistulas, administration of adult stem cells (ASCs) derived from liposuction samples has proved a promising technique in a preceding phase II trial. We aimed to extend follow-up of these patients with this retrospective study.

Method

Patients who had received at least one dose of treatment (ASCs plus fibrin glue or fibrin glue alone) were included. Adverse events notified since the end of the phase II study were recorded. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) criteria were used to determine whether recurrence of the healed fistula had occurred.

Results

Data were available for 21 out of 24 patients treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue and 13 out of 25 patients treated with fibrin glue in the phase II study. Follow-up lasted a mean of 38.0 and 42.6 months, respectively. Two adverse events unrelated to the original treatment were reported, one in each group. There were no reports of anal incontinence associated with the procedure. Of the 12 patients treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue who were included in the retrospective follow-up in the complete closure group, only 7 remained free of recurrence. MRI was done in 31 patients. No relationship was detected between MRI results and the clinical fistula status, independent of the treatment received.

Conclusions

Long-term follow-up reaffirmed the very good safety profile of the treatment. Nevertheless, a low proportion of the stem cell-treated patients with closure after the procedure remained free of recurrence after more than 3 years of follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A promising option in the treatment of complex perianal fistulas, whether of cryptoglandular origin or associated with Crohn’s disease, is the administration of adult stem cells (ASCs) into the fistulous tract. In a proof-of-concept study in a patient with rectovaginal fistula associated with Crohn’s disease, refractory to other treatments, complete closure was obtained by implanting stem cells derived from adipose tissue into the fistulous tract and sealing with fibrin glue [1]. In 2004, promising outcomes were also obtained in a subsequent phase I study in eight fistulas in four patients with Crohn’s disease [2]. A randomized phase II study was then undertaken, with fibrin glue as the control group (NCT00115466) [3]. The study included 50 patients, 49 of whom finally underwent the study procedure (24 in the ASC plus fibrin glue group and 25 in the fibrin glue alone group). ASCs were used at a dose of 20 million cells in the first administration and 40 million cells in the second administration, if needed. Significant differences between groups were obtained for the primary efficacy outcome measure (complete closure) at 8 weeks after a last implantation. Closure was maintained in 17 (71%) of 24 patients who received ASCs in addition to fibrin glue after 8 weeks and in 15 (62.5%) of 24 after 1 year of follow-up, during which time no safety issues were identified.

The objective of the present retrospective study was to provide long-term follow-up of the patients included in the aforementioned phase II study, with particular emphasis on long-term safety and recurrences of healed fistulas.

Patients and methods

Patients

All patients included in the phase II study were eligible for inclusion in the present retrospective follow-up, provided they received at least one study intervention (ACS administration plus fibrin glue or fibrin glue alone in the case of patients assigned to the control arm).

Study procedure

In October 2008, the investigators reviewed the corresponding medical records of the patients from the final visit onwards of the phase II study (phase II patient enrollment lasted from October 2004 to March 2005). Patients were then invited to attend a follow-up visit at the site where they had participated in the phase II study. A detailed clinical history was taken. The efficacy outcome in the phase II study was reported as complete closure, defined as re-epithelization and no suppuration through the external opening, and no closure, defined as lack of re-epithelization. Adverse events since the final visit of the preceding phase II study were reported according to standard regulatory definitions (serious or not, severity, causality) and could include both clinical and laboratory events.

In the medical history, the investigator also attempted to obtain information on treatments received by the patients since the last visit of the phase II study, specifically, whether they had received antitumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy (infliximab/adalimumab), antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and other treatments taken to treat perianal fistulas (and Crohn’s disease, if applicable). Additionally, information was collected on surgical procedures due to Crohn’s disease and/or fistulas.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was done to assess the status of the treated fistula, as well as to identify any new fistulas. Patients with Crohn’s disease underwent an assessment of their disease using the Montreal classification [4]. All patients provided informed consent to allow the collection and analysis of data and the MRI procedure. The study was approved by the relevant ethics committee.

The primary endpoint of the study was the number of adverse events. Long-term efficacy was assessed using the clinical and MRI status of the treated fistula (recurrence or not).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (number and percentage for categorical variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables) were calculated for the study outcome variables.

Results

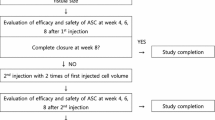

In the phase II study, 24 patients were treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue and 25 patients were treated with fibrin glue alone. Of these, 21 originally treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue and 13 originally treated with fibrin were recruited for the present retrospective follow-up analysis (Fig. 1).

Flowchart of patients included in the phase II study and the retrospective follow-up. ASCs adipose-derived adult stem cells, C fistula closed, FG fibrin glue, NC fistula not closed. a Closure after a surgical procedure. b This number was erroneously reported as 4 in the publication of the phase II results [3]

Two of the patients included in the present retrospective analysis had achieved complete closure after the experimental procedure, but their fistulas had relapsed after 1 year of follow-up (Fig. 1). The outcomes of the procedures at the last visit of the first study are presented in Table 1. Overall, complete closure at the beginning of this follow-up study was reported in 12 out of 21 patients treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue and in 3 out of 13 of those treated with fibrin glue alone.

The mean (SD) duration of follow-up was 38.0 (2.8) months for those randomized to ASCs plus fibrin glue and 42.6 (2.4) months for those randomized to fibrin glue alone (approximately 40 months for the overall sample). All patients were Caucasian, and 19 were women. These characteristics were similar to those of the overall sample of the reference phase II study (Table 2). Thirty patients had a complex perianal fistula and 4 had a rectovaginal fistula. Just under a quarter of the patients in each group of the retrospective study had Crohn’s disease.

Safety outcome

Only two adverse events were reported during the follow-up period of this retrospective study—an ischiorectal abscess in a patient treated originally with fibrin glue alone and a perianal abscess in a patient treated originally with ASCs plus fibrin glue (both toxicity grade I). These events occurred at 13 and 21 months after the original treatment, respectively. In both cases, the investigator considered these events to be unrelated to the study treatment because a long period has elapsed between the procedure and the onset of the event. Abscesses are also common events in such patients, even when untreated. No neoplastic developments were reported. The study procedure was not associated with anal incontinence in any of the patients.

Efficacy outcomes

During retrospective follow-up of the patients with complete closure, 7 out of 12 treated originally with ASCs plus fibrin glue and 2 out of 3 patients treated originally with fibrin glue alone remained free of recurrence. In the ASCs plus fibrin glue arm, both patients with rectovaginal fistulas and 3 out of 10 with perianal fistulas experienced recurrence.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of patients included in the retrospective follow-up with fistula closure at various time points in the study (at 8 weeks after the procedure, at the end of phase II follow-up after 1 year, and at the end of retrospective follow-up). At the end of retrospective follow-up (approximately 4 years after the procedure), one third of the patients who received ASCs had a closed fistula and never had a recurrence compared to 15% of those who received fibrin glue alone.

Percentage of patients with fistula closure among patients included in the retrospective analysis as the denominator (n = 21 for the adult stem cell [ASC] group and n = 13 for the fibrin glue [FG] alone group). Fistulas healed after procedures performed outside the phase II study are not included in this figure

Patients who required further surgical procedures were considered as treatment failure. During retrospective follow-up, six patients in the fibrin glue arm required an additional surgical procedure. None of these six patients had a closed fistula at the end of the phase II study. Surgery was successful in one case. Among patients who received ASCs, seven patients underwent a further operation; six were treatment failures and one had a fistula considered healed. In these patients, surgery healed three additional fistulas.

Of the four non-Crohn’s patients treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue with recurrence of their fistula after complete closure, one received antibiotics (metronidazole).

MRI outcomes

In three cases, MRI was not performed due to patient decision. Images suggestive of fistulas were found in 29 patients, although there was no apparent relationship with the clinical status of the fistula or the treatment received. Only in two patients were images of fistulas not detected; nevertheless, both had a suppurative external orifice. Abscesses and inflammation related to fistula status were detected in only three patients.

Crohn’s patients

Of the 14 patients with Crohn’s disease who were treated in the original phase II study (7 in each treatment arm), data were available for 8 in this retrospective analysis (5 treated originally with ASCs plus fibrin glue and 3 with fibrin glue alone; Table 1). At the end of the preceding study, complete closure had been reported in two out of five in the ASCs plus fibrin glue arm and one out of three in the fibrin glue alone arm. During retrospective follow-up, one recurrence of the treated fistula was reported in a patient in the ASC plus fibrin glue arm. This patient received infliximab for the recurrence. One new fistula was reported in a patient in the ASCs plus fibrin glue arm and was treated with infliximab.

During follow-up, six of the eight Crohn’s patients received infliximab. One of the remaining two Crohn’s patients received an immunosuppressant (azathioprine), while the other received mesalazine. The information available does not allow us to determine whether these medications were given specifically for fistulizing Crohn’s disease or for the underlying Crohn’s disease.

Discussion

The procedure employed in the phase II study used autologous ASCs isolated from a sample of fatty tissue obtained in a liposuction procedure and subsequently expanded [3]. Given that the cell samples are derived from the patient’s own body, safety problems were not anticipated [5]. Indeed, after 1 year of follow-up in the original phase II study, 4 out of 49 patients (8.1%) had 6 adverse events considered related to the treatment (purulent secretion, rectal bleeding, and pyrexia), although these all occurred in the control arm. While these findings supported the safety of the procedure, certain events such as neoplastic developments may only become apparent after longer follow-up periods. The present retrospective analysis—which extended total follow-up to approximately 4 years—reported no neoplastic developments. To our knowledge, this period is longer than the period of follow-up available for other ASC therapies. We also note that the first patient treated with ASCs for a rectovaginal fistula in the proof-of-concept study in 2002 [1] is currently free of neoplastic processes or other conditions, despite having undergone further ASC administrations under off-label use. In an attempt to further confirm that neoplastic processes are not a concern with ASC therapy, we have examined biopsies taken from the fistula region (results pending publication). Histology revealed no evidence of neoplastic structures.

No other safety concerns were identified. Only two adverse events were reported, neither considered related to the original study procedure. These events were considered as not related in view of the long time that elapsed between the procedure and the event and also the fact that abscesses are common events in patients with perianal fistulas, providing a likely alternative cause.

When evaluating the safety of an intervention, it is also necessary to assess the safety relative to other procedures. For fistulas of cryptoglandular origin treated by surgery, there is a risk of anal incontinence. In a study of 310 patients who underwent surgery (fistulotomy and rectal advancement flap) for anal incontinence, van Koperen et al. [6] reported soiling in 40% of the cases. In our study, ASC administration was not associated with any cases of anal incontinence. In the case of fistulizing Crohn’s disease, the current mainstay therapy is the antitumor necrosis factor-alpha agent infliximab [7]. Long-term therapy with infliximab (as would be used in maintenance regimens) is generally well tolerated, although clinicians are urged to be particularly vigilant for rare but serious adverse events such as serum sickness-like reaction, opportunistic infection and sepsis, and autoimmune disorders [8].

The preceding phase II study yielded promising efficacy results in a number of different types of Crohn’s and non-Crohn’s-related perianal fistula [3]. Overall, closure was achieved in 17 out of 24 patients treated with ASCs plus fibrin glue (after one or two administration) compared to 3 out of 25 patients treated with fibrin glue alone (erroneously reported as four patients in the original publication on the phase II study [3]). The definition of healing and the characteristics of the patient samples vary from study to study, thereby making comparisons between studies more difficult. Thus, although there is a large difference in healing rate for fibrin glue between the reference phase II study and that reported by Lindsey et al. [9] (69%), the definition of closure was more strict in our phase II study.

Although fistula closure is the primary goal of treatment, it is also important that closure is sustained not only because it reflects the long-term efficacy of treatment but also because recurrences are traditionally considered more difficult to treat subsequently by surgery. The long-term results of this retrospective study showed that 7 out of 12 patients with fistula closure after treatment with ASCs plus fibrin glue were free of recurrence over a period of 3 years.

Few data are available on follow-up of fistulas once healed, and the follow-up studies that have been done are mainly in patients with Crohn’s disease. We note that, in a placebo-controlled study of infliximab maintenance therapy in patients with fistulizing Crohn’s disease who achieved closure after open-label infliximab induction therapy, approximately 30% of patients in the placebo arm and 60% in the infliximab arm had sustained response after 54 weeks [10]. Recurrence rates after response to cyclosporine in patients with fistulizing Crohn’s disease have also been reported to be high—75% after 10 months follow-up—even with continued maintenance therapy [11]. In a long-term follow-up (52 weeks) of perianal fistula repair using fibrin glue reported by Cintron et al. [12], the mean time to recurrence was reported as 3.3 (1.7) months. In their series of 70 patients with high perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin, van Koperen et al. [9] reported a recurrence rate of 21% for the patients at a median of 76 months after the rectal advancement flap procedure. Meaningful comparison with the patients in our study is difficult, given differences in the definition of closure alluded to above, possible differences in the characteristics of the patients treated (patients included in the phase II study by definition had failed other therapies [3] and so might be considered to be more difficult to treat), and the small numbers of patients. Nevertheless, on a qualitative level, our results are promising. Breakdown of recurrence rates by type of fistula show that both rectovaginal fistulas that had healed at the end of the phase II study had recurred. This type of fistula is notoriously difficult to treat [13] and recurrences are a common problem.

Although these results are promising, there might be room for improvement. The well-known anti-inflammatory activity of ASCs is thought to be one mechanism by which they help improve healing [14]. The doses employed in this phase II study were 20 million cells for the first procedure and 40 million for the second procedure, and therefore, it is likely that this homogeneous amount of cells could be insufficient in some of the cases. Fistulas usually have multiple tracks involving an extensive area which cannot always be adequately treated with this small amount of product.

In the literature, there is insistence on the importance of a preoperative evaluation MRI [15], but we have observed that MRI results do not always correlate with the clinical reality and further analysis will be performed to give scientific support to this observation. Tougeron et al. agree with this in a recent study [16].

A major weakness of the present study is that only 13 patients (out of 25 included in the phase II study) originally treated with fibrin glue alone were included in the retrospective follow-up. The patients not included were mainly those whose fistulas failed to close during treatment, many of whom opted for surgical procedures in their reference hospital, which did not participate in the study. Although telephone contact was made with almost all these patients, many live far away from the study hospitals and so declined the invitation to participate because the study protocol required attendance for an MRI procedure. Given that many were disappointed that they had not received active treatment, they were reluctant to make the effort to travel without any immediate benefit to themselves. In as far as it is ethical to include data from these patients without their informed consent, we can affirm that we have no indications that the fistulas had healed in these patients. For the purposes of analysis of recurrence, however, most of the patients treated with fibrin glue alone who achieved complete closure in the phase II study were included. These numbers are, however, too small for meaningful comparisons between groups.

In summary, after approximately 4 years of follow-up of patients with perianal fistulas who participated in the randomized phase II study comparing the administration of ASCs with instillation of fibrin glue alone, no new safety issues were identified, which confirms the excellent safety and tolerability profile of eASCs. The small number of patients and the limitations of the study prevent any firm conclusions about efficacy from being drawn. Nevertheless, the qualitative results were promising.

References

García-Olmo D, García-Arranz M, García LG, Cuellar ES, Blanco IF, Prianes LA et al (2003) Autologous stem cell transplantation for treatment of rectovaginal fistula in perianal Crohn’s disease: a new cell-based therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis 18(5):451–454

García-Olmo D, García-Arranz M, Herreros D, Pascual I, Peiro C, Rodríguez-Montes JA (2005) A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn’s fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum 48(7):1416–1423

Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, Pascual JA, Del-Valle E, Zorrilla J et al (2009) Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: a phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum 52(1):79–86

Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR et al (2005) Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 19(Suppl A):5–36

Gimble J, Guilak F (2003) Adipose-derived adult stem cells: isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential. Cytotherapy 5(5):362–369

van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Bakx R, Reitsma JB, Slors JFM (2008) Long-term functional outcome and risk factors for recurrence after surgical treatment for low and high perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin. Dis Colon Rectum 51(10):1475–1481

Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA et al (1999) Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 340(18):1398–1405

Parsi MA, Lashner BA (2004) Safety of infliximab: primum non nocere. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease: the Mayo Clinic experience in 500 patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 10(4):486–487

Lindsey I, Smilgin-Humphreys MM, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJM, George BD (2002) A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 45(12):1608–1615

Sands BE, Blank MA, Patel K, van Deventer SJ (2004) Long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: response to infliximab in the ACCENT II Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2(10):912–920

Gurudu SR, Griffel LH, Gialanella RJ, Das KM (1999) Cyclosporine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: short-term and long-term results. J Clin Gastroenterol 29(2):151–154

Cintron JR, Park JJ, Orsay CP, Pearl RK, Nelson RL, Sone JH et al (2000) Repair of fistulas-in-ano using fibrin adhesive: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 43(7):944–949, discussion 949–950

Levy C, Tremaine WJ (2002) Management of internal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 8(2):106–111

González MA, Gonzalez-Rey E, Rico L, Büscher D, Delgado M (2009) Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental colitis by inhibiting inflammatory and autoimmune responses. Gastroenterol 136(3):978–989

Sahni VA, Ahmad R, Burling D (2008) Which method is best for imaging of perianal fistula? Abdom Imaging 33(1):26–30

Tougeron D, Savoye G, Savoye-Collet C, Koning E, Michot F, Lerebours E (2009) Predicting factors of fistula healing and clinical remission after infliximab-based combined therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci 54(8):1746–1752

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following colleagues for their invaluable help during the course of this study: Dr. José Antonio Pascual, M.D. (Department. of Surgery, Doce de Octubre University Hospital, Madrid, Spain), Dr. Emilio Del-Valle, M.D., and Dr. Jaime Zorrilla, M.D. (Department of Surgery, Gregorio Marañón University Hospital, Madrid, Spain) for their assistance in the patient follow-up; Dr. Jorge Alemany, Dr. Maria Pascual, and Dr. Gemma Fernandez (Cellerix S.A., Madrid) for their contribution to the initial design; and Dr. Gregory Morley for the editorial support.

Financial disclosure and conflicts of interest

This clinical trial has been sponsored by Cellerix S.L. Damian García-Olmo is a holder of the UAM–Cellerix Chair of Cell Therapy and Regenerative Medicine to which Cellerix contributes 40,000€ per year. UAM and Cellerix S.A. share patent rights to Cx401. García-Olmo is a member of the advisory board of Cellerix S.A. M. Garcia-Arranz and D. García-Olmo are inventors in two patents related to Cx401 entitled “Identification and isolation of multipotent cells from non-osteochondral mesenchymal tissue” (10157355957US) and “Use of adipose tissue-derived stromal stem cells in treating fistula” (US11/167061).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) granted Cx401 (autologous expanded adipose-derived adult stem cells—eASCs) “orphan drug” status in 2005 for the treatment of anal fistula (Orphan Designation EU Number EU/3/05/303).

This is a randomized clinical trial.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guadalajara, H., Herreros, D., De-La-Quintana, P. et al. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing adipose-derived adult stem cell administration to treat complex perianal fistulas. Int J Colorectal Dis 27, 595–600 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-011-1350-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-011-1350-1