Abstract

Background

We do not routinely discontinue clopidogrel before colonoscopy because we have judged the cardiovascular risks of that practice to exceed the risks of post-polypectomy bleeding (PPB).

Aims

The aim of this study was to compare the rates of PPB for clopidogrel users and non-users.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, case–control study of patients who had colonoscopic polypectomy at our VA hospital from July 2008 through December 2009. We compared the frequency of delayed PPB (within 30 days) for patients on uninterrupted clopidogrel therapy with patients not taking clopidogrel. To minimize confounding from differences between groups in conditions that might contribute to PPB, propensity scoring was used to match clopidogrel users with controls based on numerous factors including age, aspirin use, number and size of polyps removed.

Results

A total of 1,967 patients had polypectomy during the study period; 118 were on clopidogrel and 1,849 were not. Logistic regression analysis revealed no significant difference in frequency of PPB between clopidogrel users and non-users (0.8% vs. 0.3%, P = 0.37, unadjusted OR = 2.63, 95% CI 0.31–22). Matched analyses using propensity scoring also revealed no significant difference in PPB rates between clopidogrel users and non-users (0.9% vs. 0%, P = 0.99).

Conclusions

The delayed PPB rate for our patients on clopidogrel was less than 1%, and PPB rates did not differ significantly between users and non-users. Our conclusions are limited by differences in therapeutic methodology between the groups, and our findings are most applicable to small polyps (<1 cm). We speculate that cardiovascular risks of routinely discontinuing clopidogrel before elective colonoscopy may exceed any excess risk of PPB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It seems reasonable to assume that medications prescribed to interfere with platelet function might increase the risk of bleeding after invasive endoscopic procedures like polypectomy [1–3]. Based on that assumption, it was once common practice for physicians to discontinue aspirin treatment for patients scheduled for elective colonoscopy. Subsequent investigations found no increased risk of post-polypectomy bleeding in patients having colonoscopy who continued their aspirin therapy [4], and the American Society of Gastroenterology (ASGE) eventually published guidelines stating that endoscopic polypectomy can be performed safely in patients taking aspirin. Nevertheless, the ASGE’s current guidelines still suggest postponing elective procedures or discontinuing thienopyridines such as clopidogrel, if possible, prior to high risk procedures, like colonoscopy with polypectomy, for fear that polypectomy will be complicated by hemorrhage [5]. This recommendation is based on inference and expert opinion, however, not on data from clinical studies. Moreover, from a practical standpoint, it is difficult to know in most patients undergoing screening or surveillance colonoscopy whether a high risk intervention, like polypectomy, will be required and therefore many units discontinue agents like clopidogrel routinely prior to colonoscopy.

Until this year, there were no published reports on the risk of bleeding from polypectomy for patients who continued to take a thienopyridine like clopidogrel at the time of colonoscopy. Singh et al. recently published a retrospective study assessing the post-polypectomy bleeding rate in patients on uninterrupted clopidogrel therapy [6]. They found a higher rate of delayed bleeding in patients continued on clopidogrel (3.5% vs. 1% for patients not taking clopidogrel), but they attributed this increased risk to the fact that the patients on clopidogrel also were taking aspirin and/or NSAIDs. The risk of post-polypectomy bleeding due to clopidogrel itself remains unclear.

Clopidogrel is commonly used for the prevention of coronary stent thrombosis, prevention of myocardial ischemic events and cerebrovascular accidents. Indeed, the biggest risk factor that has been identified for stent thrombosis and its associated cardiac consequences is discontinuation of clopidogrel [7]. For many patients in our VA Medical Center who have been scheduled for elective colonoscopy, we have deemed the cardiovascular risks of discontinuing clopidogrel to exceed the risks of post-polypectomy bleeding and, therefore, have not stopped clopidogrel before the procedure. Moreover, in the last few years, the use of hemoclips has become routine during endoscopy and we have often elected to place hemoclips prophylactically to prevent bleeding in our patients who are on clopidogrel. However, the efficacy and safety of these practices have not been evaluated in formal investigations. In this retrospective cohort study, we explored the risk of post-polypectomy bleeding for patients who underwent polypectomy while continuing clopidogrel therapy.

Methods

Study Design

A retrospective case–control study was performed on all patients who underwent elective colonoscopy with polypectomy at the Dallas VA Medical Center between July 2008 and December 2009. This study was approved by the Dallas VA Medical Center’s institutional review board.

Identification of Cases and Controls

The Dallas VA gastroenterology endoscopy database (ProVationMD) was reviewed to identify all patients who underwent elective colonoscopy with polypectomy between July 2008 and December 2009. In order to identify cases, the electronic medical charts of all patients identified as having had polypectomy were then reviewed for use of clopidogrel at the time of their colonoscopy. Patients’ continued use of clopidogrel through the time of their colonoscopy was verified by review of medical records including referring physician’s notes, medication reconciliation notes, pharmacy records, the colonoscopy consult, pre-procedure notes (including questionnaires on medication use on the day of the procedure), and colonoscopy reports. Patients who either were not taking clopidogrel at all or who held their clopidogrel prior to the procedure comprised the control group. We defined holding of clopidogrel therapy to be cessation of medication consumption for at least 5 days prior to procedure. Patient who were on warfarin therapy were excluded from the study.

Data Collection

Demographic Data

Each patient’s medical chart was reviewed for age, sex, race, and co-morbidities including chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular disease (cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack).

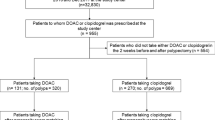

Medication Use

Medication records were reviewed for use of clopidogrel, aspirin, NSAIDs, and warfarin within the 2 weeks preceding the colonoscopy. Data collected included indication for clopidogrel, dose of medications, whether or not the medication was held prior to procedure, and if so, how long prior to the procedure it had been held. Aspirin and NSAIDs are not routinely held prior to colonoscopy at our institution. Moreover, after polypectomy, aspirin and clopidogrel are not routinely discontinued.

Procedure Data

Colonoscopy records were reviewed and data collected on indication for colonoscopy, number of polyps removed, polyp locations, size, morphology, removal technique (cold forceps, hot/cold snare), complications, hemostatic techniques employed (i.e. clips used), and pathology.

Post-Polypectomy Bleeding

The primary outcome of interest was delayed post-polypectomy bleeding. This was defined as blood per rectum occurring within 30 days of the procedure and requiring hospitalization or treatment.

The occurrence of delayed post-polypectomy bleeding was determined by review of multiple sources of information. At the Dallas VA Medical Center, patients are phoned within 48 h of their colonoscopy to assess for any possible procedurally-related complications. This is documented in the medical record. Additionally, the medical record for a minimum of 30 days after colonoscopy was reviewed for each patient; this included visits to primary care providers, subspecialty clinics, pharmacy notes, telephone records, emergency room visits, and any hospitalization related notes (admission notes, progress notes, and discharge notes).

For those patients who were found to have had post-polypectomy bleeding, additional data were collected including the time from colonoscopy to onset of bleeding, length of hospital stay, change in hematocrit, necessity and quantity of blood transfusion, and intervention required for hemostasis (i.e., angiography, repeat colonoscopy, placement of clips).

Case Matching and Propensity Scoring

Propensity score matching was used in order to adjust for group selection bias between our cases (clopidogrel users) and controls. Propensity scores were calculated by using multivariate logistic regression with the group of patients on clopidogrel as the dependent variable and our set of individual characteristics as the predictors. Propensity scores were used to match every case (clopidogrel user) to a control based on variables that may independently predict the risk of post-polypectomy bleeding. These were identified and matched between the two groups. These included age, ethnicity, sex, aspirin use, NSAID use, presence of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Data Analysis

Data between the clopidogrel cohort and controls were compared. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for post-polypectomy bleeding, including clopidogrel use. After identification of all characteristics that may have accounted for differences between the groups, the two groups were compared for differences in age, ethnicity, gender, NSAID use, aspirin use, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, lung disease, renal disease, number of polyps, largest polyp size, and removal technique (cold forceps, hot snare, or cold snare).

Given the large number of controls as compared to clopidogrel users, propensity matching was used to reduce bias. Propensity scores were calculated as described above. For the matched analysis, differences between matched pairs on bleeding were evaluated using a McNemar test.

Results

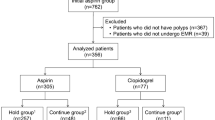

A total of 1,967 patients were identified who underwent polypectomy. Of these, there were 118 cases (patients on uninterrupted therapy with clopidogrel) and 1,849 controls (patients not on clopidogrel at the time of polypectomy) (Fig. 1).

Baseline Characteristics

Our study populations were significantly different in regards to average age (64.9 years in the clopidogrel users and 62.4 years in the controls), gender (118/118 male in clopidogrel users and 1,779/1,849 male in controls), and ethnicity (101/118 white in clopidogrel users and 1,234/1,849 white in controls). There were also significant differences in unadjusted comparisons with regard to co-morbid coronary artery disease (94.1% in the clopidogrel users vs. 24.2% in the controls), peripheral vascular disease (14.4% vs. 4.5%), cerebrovascular disease (10.2% vs. 5.7%), lung disease (24.6% vs. 13.4%), and chronic kidney disease (16.1% vs. 6.7%). There were additional significant differences in unadjusted comparisons of concomitant aspirin use (78.8% of clopidogrel users vs. 27.9% of controls), and concomitant NSAID use (7.6% vs. 14.7%) (Table 1).

The majority of patients in both groups were referred for average-risk screening, polyp surveillance and positive fecal occult blood testing (Fig. 2). In the clopidogrel users, the large majority were on clopidogrel therapy because of a coronary stent (81% of the clopidogrel users); the rest were divided among CAD without a stent (8%), CVA/TIA (7%), peripheral stent (3%), and cardioprotection (1%).

Polypectomy Data

A total of 360 polypectomies were performed in the 118 patients on uninterrupted clopidogrel therapy and 5,671 polypectomies were performed in the 1,849 patients in the control group. The average number of polyps removed per patient was not significantly different between the two groups (3.05 ± 2.7 in clopidogrel users vs. 3.08 ± 2.8 in controls) and the median number of polyps removed in both groups was two. The greatest number of polyps removed in a patient on clopidogrel was 16; the largest polyp removed was 40 mm. In the control group, the greatest number of polyps removed in a single patient was 24; the largest polyp removed was 100 mm. There was no significant difference in the average size of polyps removed per patient between our two groups (6.5 ± 5.6 mm clopidogrel vs. 7.1 ± 6.6 mm controls). The median size of polyp removed was 5 mm in both groups. There was also no difference between the two groups with respect to the number of patients who had polyps >10 mm removed (14.4% clopidogrel vs. 20% controls). The majority of polyps were removed by cold forceps (255/360 [70.8%] in clopidogrel users vs. 3,492/5,671 [61.6%] in controls), followed by hot snare (93/360 [25.8%] vs. 2,006/5,671 [35.4%]), and then cold snare (9/360 [2.5%] vs. 110/5,671 [1.9%]). There was no statistically significant difference between groups for any of these removal techniques. In the clopidogrel users group, 26/118 (22%) had hemoclips deployed on polypectomy sites as compared to 190/1,849 (10.3%) in the controls (P = 0.0001, chi-squared test) (Table 1).

Post-Polypectomy Bleeding

There was one post-polypectomy bleed in the clopidogrel users (0.85%) and six in the control group (0.32%). Using the whole sample of 1,967 subjects, a logistic regression analysis of clopidogrel use on delayed bleed indicated no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.37, unadjusted OR = 2.63, 95% CI 0.31–22.0).

Characteristics of patients who had delayed post-polypectomy bleeding are summarized in Table 2. The single patient on clopidogrel who experienced a post-polypectomy bleed was also on full-dose aspirin therapy (325 mg). He had a total of seven polyps removed; the largest was 8 mm which was removed by hot snare. At the time of the index colonoscopy, this post-polypectomy site was prophylactically clipped, though there was no immediate bleeding at the time of polypectomy. Eight days later, the patient noted the onset of blood per rectum and sought medical attention. During the hospitalization, it was noted that his hematocrit had dropped from 42 to 29. Repeat colonoscopy identified the post-polypectomy site of the 8 mm polyp as the bleeding lesion, and it was clipped with three additional devices. The patient did not have any adverse events associated with his bleed and did not receive blood transfusion. The patient was discharged uneventfully after 2 days.

The average age in our control patients who experienced delayed post-polypectomy bleeding was 67.1 years. Of the control patients, five were on either aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The average number of polyps removed was 2.7 (range 1–7); the average size of polyp removed was 12.9 mm (range 5–25 mm). Four patients had polyps >10 mm removed. Six of seven (85.7%) polyps were removed with either hot snare or combination saline injection and hot snare. Five of seven bleeds were within 48 h, and the average length of stay in the hospital was 1.3 days. Four patients required blood transfusion (each received two units of packed red blood cells).

Case Matched Analysis

Because of the statistically significant differences between our cohorts in covariates that could potentially result in differences in the post-polypectomy bleeding rate irrespective of clopidogrel therapy, we used propensity scoring to minimize any effects of selection bias on study outcomes. Of the original 118 clopidogrel patients, 111 were able to be matched to a control based on age, ethnicity, gender, NSAID use, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, lung disease, renal disease, number of polyps, largest size polyp, and polyp removal technique (cold forceps, hot snare, and cold snare) (Table 3).

For the matched analysis, differences between matched pairs on bleeding (111 pairs) were evaluated using a McNemar test. There was 1 in 111 cases (0.9%) with delayed post-polypectomy bleeding in the clopidogrel group, and none in the control group. When matched on gender, age, ethnicity, NSAID use, aspirin use, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and renal disease, there still was no significant difference between the groups in the rate of post-polypectomy bleeding (P = 0.99, χ²(1) = 0.00, ns).

Discussion

Colon cancer is the third leading cause of new cancer diagnoses and of cancer deaths in the United States. Nevertheless, the frequency of colon cancer pales when compared to the frequency of heart disease in the general population [8]. Most patients with known heart disease are over 50 years of age and, therefore, in the group of patients for whom colon cancer screening often is advised. Many of these patients are taking clopidogrel and other thienopyridines.

The most frequent indication for thienopyridine use is for prevention of coronary stent thrombosis. This is a very serious complication of percutaneous coronary intervention, as evidenced by one study that found a case-fatality rate of 45% for patients who developed stent thrombosis [9]. The greatest recognized risk factor for this lethal complication is discontinuation of thienopyridines [9, 10]. These agents also are used frequently for the prevention of vascular ischemic events in patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis. Such vascular ischemic events (e.g. myocardial infarction, stroke) also can be lethal or can result in severe disability. Post-polypectomy bleeding, in contrast, usually is not life-threatening and usually can be controlled with minimally invasive therapies. In our practice approximately 2 years ago, therefore, we made a decision not to discontinue clopidogrel therapy routinely prior to elective colonoscopy. In this study, we have documented the safety of this policy.

In our study of 1,967 patients who had colonoscopic polypectomy, 118 were on clopidogrel at the time of the procedure. We found no significant difference in the frequency of delayed post-polypectomy bleeding between clopidogrel users and controls (0.8% vs. 0.3%, P = 0.37, unadjusted OR = 2.63, 95% CI 0.31–22). We did find significant differences between clopidogrel users and controls in the frequency of coronary artery disease (94.1% clopidogrel users vs. 24.2% controls), aspirin use (78% clopidogrel users vs. 27.9% controls), age (64.9 in clopidogrel users vs. 62.4 in controls), and lung disease (24.6% clopidogrel users vs. 13.4% controls), factors which have been associated with an increased frequency of post-polypectomy bleeding in some earlier studies [11, 12] (Table 1). We used propensity scoring to match our clopidogrel cases with controls for these attributes, and the matched analyses also revealed no significant difference in bleeding rates between clopidogrel users and controls (0.9% vs. 0%, P = 0.99). Furthermore, the rate of post-polypectomy bleeding that we documented in our patients on clopidogrel is well within the range of post-polypectomy bleeding rates that have been reported for patients who do not take clopidogrel (up to 2.3%) [13].

Our study has a number of limitations, most notably its retrospective nature. Our patients routinely are contacted by telephone 48 h after colonoscopy, but not again after that time. Therefore, we may not have identified patients who bled at times beyond 48 h. To minimize this problem, for all clopidogrel patients we reviewed their subsequent hospital visits, including primary care or subspecialty clinic follow-up and emergency room visits, along with any additional documentation recorded by nurses or other staff members for a period of 30 days after the procedure. Another weakness of our study was that endoclip placement was not mandated by specific criteria, but rather was performed at the discretion of the endoscopist. These clips were used more often for the patients taking clopidogrel, and this may have biased our post-polypectomy bleeding rates to be lower than might be expected. It is not clear that endoclips prevent post-polypectomy bleeding, however, and it is interesting to note that our only post-polypectomy bleed in the clopidogrel group occurred from a polypectomy site that had been clipped prophylactically. An additional limitation is that our total number of post-polypectomy bleeds was small, which limited the power of our study. While statistically we found no difference in post-polypectomy bleeds in patients continued on clopidogrel compared to those not on this medication, given the wide confidence intervals, a type II error cannot be excluded. Moreover, most of the polyps removed were not at exceptionally high risk for bleeding (i.e. not removed by hot snare and/or size not >1 cm), further limiting the power to assess the contribution of clopidogrel to PPB in high-risk patients. Finally, the technique of polypectomy may have varied, as there were a number of endoscopists with a wide range of experience (first year GI fellow to senior attending) performing the procedure.

In conclusion, we found that the overall post-polypectomy bleeding rate in patients continuing to take clopidogrel at the time of colonoscopy was less than 1%, and did not differ significantly from that for patients not on clopidogrel. Moreover, the post-polypectomy bleeding that did occur in both patient groups was not life-threatening and was treated medically or endoscopically without long-term sequelae. Our study suggests that any increased risk of post-polypectomy bleeding associated with clopidogrel use is small. Given that the majority of polyps removed were small and removed by cold forceps, our data is most applicable to this group of patients and the safety of removing larger polyps without stopping clopidogrel therapy remains less clear. Moreover, the role played by prophylactic hemoclipping is still uncertain and may have biased our results. Additional prospective studies to further define the rate of post-polypectomy bleeding in patients on clopidogrel are needed.

References

Nakajima H, Takami H, Yamagata K, Kariya K, Tamai Y, Nara H. Aspirin effects on colonic mucosal bleeding: implications for colonic biopsy and polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1484–1488.

Basson MD, Panzini L, Palmer RH. Effect of nabumetone and aspirin on colonic mucosal bleeding time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:539–542.

Timothy SK, Hicks TC, Opelka FG, Timmcke AE, Beck DE. Colonoscopy in the patient requiring anticoagulation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1845–1848.

Yousfi M, Gostout CJ, Barron TH, et al. Postpolypectomy lower gastrointestinal bleeding: potential role of aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1785–1789.

Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, et al. [ASGE Standards of Practice Committee] Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–1070.

Singh M, Mehta N, Murthy UK, et al. Postpolypectomy bleeding in patients undergoing colonoscopy on uninterrupted clopidogrel therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:998–1005.

Ho PM, Peterson ED, Wang L, et al. Incidence of death and acute myocardial infarction associated with stopping clopidogrel after acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2008;299:532–539.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2008.

Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005;293:2126–2130.

van Werkum JW, Heestermans AA, Zomer AC, et al. Predictors of coronary stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cadiol. 2009;53:1399–1409.

Kim HS, Kim TI, Kim WH, et al. Risk factors for immediate postpolypectomy bleeding of the colon: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1333–1341.

Sawhney MS, Salfiti N, Nelson DB, Lederle FA, Bond JH. Risk factors for severe delayed postpolypectomy bleeding. Endoscopy. 2008;40:115–119.

Veitch AM, Baglin TP, Gershlick AH, Harnden SM, Tighe R, Cairns S. Guidelines for the management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gut. 2008;57:1322–1329.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Office of Medical Research, Department of Veteran’s Affairs, Dallas, TX (L. A. Feagins) and the Harris Methodist Health Foundation, Dr. Clark R. Gregg Fund (L. A. Feagins).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feagins, L.A., Uddin, F.S., Davila, R.E. et al. The Rate of Post-Polypectomy Bleeding for Patients on Uninterrupted Clopidogrel Therapy During Elective Colonoscopy Is Acceptably Low. Dig Dis Sci 56, 2631–2638 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1682-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1682-2