Key Points

-

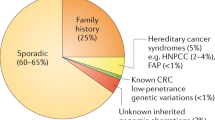

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is considered a heterogeneous disease, regarding pathogenesis and clinical behaviour

-

The suggested pathogenesis of CRC from serrated polyps has led to a paradigm shift in tumour-prevention strategies

-

Common molecular alterations associated with the serrated neoplasia pathway are a mutation in the BRAF proto-oncogene and hypermethylation of CpG islands on the promoter regions of tumour suppressor genes

-

Only limited high-quality longitudinal data are available in combination with high-quality endoscopic, histopathological and molecular data, which severely restricts elucidation of this pathway

-

However, a growing body of circumstantial evidence has been accumulated, indicating that ≥15% of all CRCs arise through the serrated neoplasia pathway

Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is considered a heterogeneous disease, both regarding pathogenesis and clinical behaviour. Four decades ago, the adenoma–carcinoma pathway was presented as the main pathway towards CRC, a conclusion that was largely based on evidence from observational morphological studies. This concept was later substantiated at the genomic level. Over the past decade, evidence has been generated for alternative routes in which CRC might develop, in particular the serrated neoplasia pathway. Providing indisputable evidence for the neoplastic potential of serrated polyps has been difficult. Reasons include the absence of reliable longitudinal observations on individual serrated lesions that progress to cancer, a shortage of available animal models for serrated lesions and challenging culture conditions when generating organoids of serrated lesions for in vitro studies. However, a growing body of circumstantial evidence has been accumulated, which indicates that ≥15% of CRCs might arise through the serrated neoplasia pathway. An even larger amount of post-colonoscopy colorectal carcinomas (carcinomas occurring within the surveillance interval after a complete colonoscopy) have been suggested to originate from serrated polyps. The aim of this Review is to assess the current status of the serrated neoplasia pathway in CRC and highlight clinical implications.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel, R., Naishadham, D. & Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin. 63, 11–30 (2013).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer 49, 1374–1403 (2013).

Winawer, S. J. et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 1977–1981 (1993).

Muto, T., Bussey, H. J. R. & Morson, B. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer 6, 2251–2270 (1975).

Arthur, J. F. Structure and significance of metaplastic nodules in the rectal mucosa. J. Clin. Pathol. 21, 735–743 (1968).

Iino, H. et al. DNA microsatellite instability in hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps: a mild mutator pathway for colorectal cancer? J. Clin. Pathol. 52, 5–9 (1999).

O'Brien, M. J. et al. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma end points. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 30, 1491–1501 (2006).

Colussi, D., Brandi, G., Bazzoli, F. & Ricciardiello, L. Molecular pathways involved in colorectal cancer: implications for disease behavior and prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 16365–16385 (2013).

Sideris, M. & Papagrigoriadis, S. Molecular biomarkers and classification models in the evaluation of the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 34, 2061–2068 (2014).

Snover, D. C., Ahnen, D. J., Burt, R. W. & Odze, R. D. in WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System Vol. 3 Ch. 8 (ed Bosman, F. T., Carneiro, F., Hruban, R. H., Theise, N. D.) 160–165 (IARC Press, 2010).

Snover, D. C. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 42, 1–10 (2011).

Boparai, K. S. et al. A serrated colorectal cancer pathway predominates over the classic WNT pathway in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 2700–2707 (2011).

East, J. E., Saunders, B. P. & Jass, J. R. Sporadic and syndromic hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colon: classification, molecular genetics, natural history, and clinical management. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 37, 25–46, v (2008).

Bettington, M. et al. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology 62, 367–386 (2013).

Oono, Y. et al. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig. Dis. Sci. 54, 906–909 (2009).

Lash, R. H., Genta, R. M. & Schuler, C. M. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J. Clin. Pathol. 63, 681–686 (2010).

Lu, F. I. et al. Longitudinal outcome study of sessile serrated adenomas of the colorectum: an increased risk for subsequent right-sided colorectal carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 34, 927–934 (2010).

Holme, O. et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with serrated polyps. Gut http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307793.

Lazarus, R., Junttila, O. E., Karttunen, T. J. & Mäkinen, M. J. The risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with serrated adenoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 123, 349–359 (2005).

Teriaky, A., Driman, D. K. & Chande, N. Outcomes of a 5-year follow-up of patients with sessile serrated adenomas. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 47, 178–183 (2012).

Carragher, L. A. S. et al. V600EBraf induces gastrointestinal crypt senescence and promotes tumour progression through enhanced CpG methylation of p16INK4a. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 458–471 (2010).

Bennecke, M. et al. Ink4a/Arf and oncogene-induced senescence prevent tumor progression during alternative colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 18, 135–146 (2010).

Leystra, A. A. et al. Mice expressing activated PI3K rapidly develop advanced colon cancer. Cancer Res. 72, 2931–2936 (2012).

Rad, R. et al. A genetic progression model of BrafV600E-induced intestinal tumorigenesis reveals targets for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Cell 24, 615–629 (2013).

Jass, J. R. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology 50, 113–130 (2007).

Toyota, M. et al. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8681–8686 (1999).

Burgess, N. G., Tutticci, N. J., Pellise, M. & Bourke, M. J. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with cytologic dysplasia: a triple threat for interval cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 80, 307–310 (2014).

Arain, M. A. et al. CIMP status of interval colon cancers: another piece to the puzzle. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105, 1189–1195 (2010).

Le Clercq, C. M. C. & Sanduleanu, S. Interval colorectal cancers: What and why. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 16, 375 (2014).

Nishihara, R. et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 1095–1105 (2013).

Hazewinkel, Y. et al. Prevalence of serrated polyps and association with synchronous advanced neoplasia in screening colonoscopy. Endoscopy 46, 219–224 (2014).

Carr, N. J., Mahajan, H., Tan, K. L., Hawkins, N. J. & Ward, R. L. Serrated and non-serrated polyps of the colorectum: their prevalence in an unselected case series and correlation of BRAF mutation analysis with the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. J. Clin. Pathol. 62, 516–518 (2009).

Rex, D. K. et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 107, 1315–1329 (2012).

Fernando, W. C. et al. The CIMP phenotype in BRAF mutant serrated polyps from a prospective colonoscopy patient cohort. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014, 374926 (2014).

Leggett, B. & Whitehall, V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 138, 2088–2100 (2010).

Rosty, C., Hewett, D. G., Brown, I. S., Leggett, B. A. & Whitehall, V. L. J. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: current understanding of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J. Gastroenterol. 48, 287–302 (2013).

Aust, D. E. & Baretton, G. B. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps)-proposal for diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch. 457, 291–297 (2010).

Vieth, M., Quirke, P., Lambert, R., von Karsa, L. & Risio, M. Annex to Quirke et al. Quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: annotations of colorectal lesions. Virchows Arch. 458, 21–30 (2011).

Abdeljawad, K. et al. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81, 517–524 (2015).

Bouwens, M. W. E. et al. Endoscopic characterization of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with and without dysplasia. Endoscopy 46, 225–235 (2014).

Wiland, H. O. et al. Morphologic and molecular characterization of traditional serrated adenomas of the distal colon and rectum. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 38, 1290–1297 (2014).

Jaramillo, E., Tamura, S. & Mitomi, H. Endoscopic appearance of serrated adenomas in the colon. Endoscopy 37, 254–260 (2005).

Tsai, J. H. et al. Traditional serrated adenoma has two pathways of neoplastic progression that are distinct from the sessile serrated pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis. Mod. Pathol. 27, 1375–1385 (2014).

Bettington, M. et al. A clinicopathological and molecular analysis of 200 traditional serrated adenomas. Mod. Pathol. 28, 414–427 (2015).

Bettington, M. et al. Critical appraisal of the diagnosis of the sessile serrated adenoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 38, 158–166 (2014).

Goldman, H., Ming, S. & Hickock, D. Nature and significance of hyperplastic polyps of the human colon. Arch. Pathol. 89, 349–354 (1970).

Cooper, H. S., Patchefsky, A. S. & Marks, G. Adenomatous and carcinomatous changes within hyperplastic colonic epithelium. Dis. Colon Rectum 22, 152–156 (1979).

Franzin, G. & Novelli, P. Adenocarcinoma occurring in a hyperplastic (metaplastic) polyp of the colon. Endoscopy 14, 28–30 (1982).

Jass, J. R. Relation between metaplastic polyp and carcinoma of the colorectum. Lancet 321, 28–30 (1983).

Williams, G. T., Arthur, J. F., Bussey, H. J. & Morson, B. C. Metaplastic polyps and polyposis of the colorectum. Histopathology 4, 155–170 (1980).

Boparai, K. S. et al. Increased colorectal cancer risk during follow-up in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome: a multicentre cohort study. Gut 59, 1094–1100 (2010).

Edelstein, D. L. et al. Serrated polyposis: rapid and relentless development of colorectal neoplasia. Gut 62, 404–408 (2013).

Ferrandez, A., Samowitz, W., DiSario, J. A. & Burt, R. W. Phenotypic characteristics and risk of cancer development in hyperplastic polyposis: Case series and literature review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 99, 2012–2018 (2004).

Hyman, N. H., Anderson, P. & Blasyk, H. Hyperplastic polyposis and the risk of colorectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 47, 2101–2104 (2004).

Rubio, C. A., Stemme, S., Jaramillo, E. & Lindblom, A. Hyperplastic polyposis coli syndrome and colorectal carcinoma. Endoscopy 38, 266–270 (2006).

Carvajal-Carmona, L. G. et al. Molecular classification and genetic pathways in hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. J. Pathol. 212, 378–385 (2007).

Jass, J. R. et al. Neoplastic progression occurs through mutator pathways in hyperplastic polyposis of the colorectum. Gut 47, 43–49 (2000).

Pino, M. S. & Chung, D. C. The chromosomal instability pathway in colon cancer. Gastroenterology 138, 2059–2072 (2010).

Chen, D. et al. BRAFV600E Mutation and its association with clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e90607 (2014).

Clancy, C., Burke, J. P., Kalady, M. F. & Coffey, J. C. BRAF mutation is associated with distinct clinicopathological characteristics in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 15, e711–e718 (2013).

Park, S.-J. et al. Frequent CpG island methylation in serrated adenomas of the colorectum. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 815–822 (2003).

Kakar, S., Deng, G., Cun, L., Sahai, V. & Kim, Y. S. CpG island methylation is frequently present in tubulovillous and villous adenomas and correlates with size, site, and villous component. Hum. Pathol. 39, 30–36 (2008).

Kim, Y. H., Kakar, S., Cun, L., Deng, G. & Kim, Y. S. Distinct CpG island methylation profiles and BRAF mutation status in serrated and adenomatous colorectal polyps. Int. J. Cancer 123, 2587–2593 (2008).

Van Engeland, M., Derks, S., Smits, K. M., Meijer, G. A. & Herman, J. G. Colorectal cancer epigenetics: complex simplicity. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1382–1391 (2011).

Bird, A. CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature 321, 209–213 (1986).

Müller, H. M. et al. Methylation changes in faecal DNA: A marker for colorectal cancer screening? Lancet 363, 1283–1285 (2004).

Lenhard, K. et al. Analysis of promoter methylation in stool: a novel method for the detection of colorectal cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3, 142–149 (2005).

Chan, A. O. O., Issa, J. P. J., Morris, J. S., Hamilton, S. R. & Rashid, A. Concordant CpG island methylation in hyperplastic polyposis. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 529–536 (2002).

Weisenberger, D. J. et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 38, 787–793 (2006).

Ogino, S., Kawasaki, T., Kirkner, G. J., Loda, M. & Fuchs, C. S. CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer: possible associations with male sex and KRAS mutations. J. Mol. Diagn. 8, 582–588 (2006).

Lee, S. et al. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancers: comparison of the new and classic CpG island methylator phenotype marker panels. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 132, 1657–1665 (2008).

Fang, M., Ou, J., Hutchinson, L. & Green, M. R. The BRAF oncoprotein functions through the transcriptional repressor MAFG to mediate the CpG Island Methylator phenotype. Mol. Cell 55, 904–915 (2014).

Suzuki, H. et al. IGFBP7 is a p53-responsive gene specifically silenced in colorectal cancer with CpG island methylator phenotype. Carcinogenesis 31, 342–349 (2010).

Kriegl, L. et al. Up and downregulation of p16Ink4a expression in BRAF-mutated polyps/adenomas indicates a senescence barrier in the serrated route to colon cancer. Mod. Pathol. 24, 1015–1022 (2011).

Farzanehfar, M. et al. Evaluation of methylation of MGMT (O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase) gene promoter in sporadic colorectal cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 32, 371–377 (2013).

Kambara, T. et al. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut 53, 1137–1144 (2004).

Samowitz, W. S. et al. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 65, 6063–6069 (2005).

Davies, H. et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417, 949–954 (2002).

Kolch, W. Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem. J. 351, 289–305 (2000).

Rajagopalan, H. et al. Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status. Nature 418, 934 (2002).

Burnett-Hartman, A. N. et al. Genomic aberrations occurring in subsets of serrated colorectal lesions but not conventional adenomas. Cancer Res. 73, 2863–2872 (2013).

Kim, K.-M. et al. Molecular features of colorectal hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenoma/polyps from Korea. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 35, 1274–1286 (2011).

Sandmeier, D., Benhattar, J., Martin, P. & Bouzourene, H. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a molecular study comparing sessile serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Histopathology 55, 206–213 (2009).

Spring, K. J. et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 131, 1400–1407 (2006).

Yang, S., Farraye, F. A., Mack, C., Posnik, O. & O'Brien, M. J. BRAF and KRAS Mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 28, 1452–1459 (2004).

Konishi, K. et al. Molecular differences between sporadic serrated and conventional colorectal adenomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3082–3090 (2004).

Chan, T. L., Zhao, W., Leung, S. Y. & Yuen, S. T. BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res. 63, 4878–4881 (2003).

Yamauchi, M. et al. Colorectal cancer: a tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut 61, 794–797 (2012).

Lochhead, P. et al. Progress and opportunities in molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal premalignant lesions. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 1205–1214 (2014).

Yamauchi, M. et al. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut 61, 847–854 (2012).

Phipps, A. I. et al. BRAF mutation status and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis according to patient and tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 1792–1798 (2012).

Hassan, C. et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 45, 842–851 (2013).

Zauber, A. A. G. et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N. Engl. J. Med. 67, 355–356 (2012).

Li, X. et al. Oncogenic transformation of diverse gastrointestinal tissues in primary organoid culture. Nat. Med. 20, 769–777 (2014).

Sawhney, M. S. et al. Microsatellite Instability in Interval Colon Cancers. Gastroenterology 131, 1700–1705 (2006).

Kahi, C. J., Hewett, D. G., Norton, D. L., Eckert, G. J. & Rex, D. K. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 42–46 (2011).

De Wijkerslooth, T. R. et al. Differences in proximal serrated polyp detection among endoscopists are associated with variability in withdrawal time. Gastrointest. Endosc. 77, 617–623 (2013).

Payne, S. R. et al. Endoscopic detection of proximal serrated lesions and pathologic identification of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps vary on the basis of center. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 1119–1126 (2014).

Hazewinkel, Y. et al. Incidence of Colonic Neoplasia in Patients with Serrated Polyposis Syndrome Who Undergo Annual Endoscopic Surveillance. Gastroenterology 147, 88–95 (2014).

Stegeman, I. et al. Colorectal cancer risk factors in the detection of advanced adenoma and colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 37, 278–283 (2013).

Qazi, T. M. et al. Epidemiology of goblet cell and microvesicular hyperplastic polyps. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 1922–1932 (2014).

Haque, T. R., Bradshaw, P. T. & Crockett, S. D. Risk Factors for Serrated Polyps of the Colorectum. Dig. Dis. Sci. 59, 2874–2889 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to researching data for the article, the discussion of content, writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.D. has received research grant support and equipment on loan from Olympus. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

IJspeert, J., Vermeulen, L., Meijer, G. et al. Serrated neoplasia—role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 12, 401–409 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2015.73

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2015.73

This article is cited by

-

Sessile serrated lesions with dysplasia: is it possible to nip them in the bud?

Journal of Gastroenterology (2023)

-

piR-823 inhibits cell apoptosis via modulating mitophagy by binding to PINK1 in colorectal cancer

Cell Death & Disease (2022)

-

Disparate age and sex distribution of sessile serrated lesions and conventional adenomas in an outpatient colonoscopy population–implications for colorectal cancer screening?

International Journal of Colorectal Disease (2022)

-

Development of a Large Colonoscopy-Based Longitudinal Cohort for Integrated Research of Colorectal Cancer: Partners Colonoscopy Cohort

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2022)

-

Real-time colorectal polyp detection using a novel computer-aided detection system (CADe): a feasibility study

International Journal of Colorectal Disease (2022)