Abstract

Background

Operative mortality traditionally has been defined as the rate within 30 days or during the initial hospitalization, and studies that established the volume–outcome relationship for pancreatectomy used similar definitions.

Methods

Pancreatectomies reported to the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) during 2007–2010 were examined for 30- and 90-day mortality. Unadjusted mortality rates were compared by type of resection, stage, comorbidities, and average annual hospital volume. Hierarchical logistic regression models generated risk-adjusted odds ratios for 30- and 90-day mortality.

Results

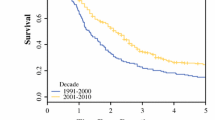

After 21,482 pancreatectomies, the unadjusted 30-day mortality rate was 3.7 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 3.4–3.9 %), which doubled at 90 days to 7.4 % (95 % CI 7.0–7.8). The unadjusted and risk-adjusted mortality rates were higher at 30 days with increasing age, increasing stage, male gender, lower income, low hospital volume, resections other than distal pancreatectomy, Medicare or Medicaid insurance coverage, residence in a Southern census division, history of prior cancer, and multiple comorbidities. The lowest-volume hospitals (<5 per year) performed 19 % of the pancreatectomies, with a risk-adjusted odds ratios for mortality that were 4.2 times higher (95 % CI 3.1–5.8) at 30 days and remained 1.9 times higher (95 % CI 1.5–2.3) at 30–90 days compared with hospitals that had high volumes (≥40 per year).

Conclusion

Mortality rates within 90 days after pancreatic resection are double those at 30 days. The volume–outcome relationship persists in the NCDB. Reporting mortality rates 90 days after pancreatectomy is important. Hospitals should be aware of their annual volume and mortality rates 30 and 90 days after pancreatectomy and should benchmark the use of high-volume hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lieberman MD, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan MF. Relation of perioperative deaths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:638–45.

Gordon TA, Burleyson, GP, Tielsch JM, Cameron JL. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure. Ann Surg. 1995;221: 43–9.

Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ. Hospital volume influences outcome in patients undergoing pancreatic resection for cancer. West J Med. 1996;165:294–300.

Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280:1747–51.

Kotwall CA, Maxwell JG, Brinker CC, Koch GG, Covington DL. National estimates of mortality rates for radical pancreaticoduodenectomy in 25,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:847–54.

Simunovic M, To T, Theriault M, Langer B. Relation between hospital surgical volume and outcome for pancreatic resection for neoplasm in a publicly funded health care system. CMAJ. 1999;160:643–8.

Killeen SD, O’Sullivan MJ, Coffey JC, Kirwan WO, Redmond HP. Provider volume and outcomes for oncological procedures. Br J Surg. 2005;92:389–402.

Janes RH, Niederhuber JE, Chmiel JS, Winchester DP, Ocwieja KC, Karnell LH, Clive RE, Menck HR. National patterns of care for pancreatic cancer: results of a survey by the Commission on Cancer. Ann Surg. 1996;223:261–72.

Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:683–90.

Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards Revised for 2013, appendix B, p. 385. Retrieved 15 February 2014 at http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/fords/fords-manual-2013.pdf.

Elixhauser A, Steiner, C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27.

Lieffers JR, Baracos VE, Winget M, Fassbender K. A comparison of Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity measures to predict colorectal cancer survival using administrative health data. Cancer. 2011;117:1957–65.

Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care. 2004;42:355–60.

Disclosure

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Swanson, R.S., Pezzi, C.M., Mallin, K. et al. The 90-Day Mortality After Pancreatectomy for Cancer Is Double the 30-Day Mortality: More than 20,000 Resections From the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol 21, 4059–4067 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4036-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4036-4