Abstract

Synopsis

Pantoprazole is an irreversible proton pump inhibitor which, at the therapeutic dose of 40mg, effectively reduces gastric acid secretion.

In controlled clinical trials, pantoprazole (40mg once daily) has proved superior to ranitidine (300mg once daily or 150mg twice daily) and equivalent to omeprazole (20mg once daily) in the short term (≤8 weeks) treatment of acute peptic ulcer and reflux oesophagitis. Gastric and duodenal ulcer healing proceeded significantly faster with pantoprazole than with ranitidine, and at similar rates with pantoprazole and omeprazole. The time course of gastric ulcer pain relief was similar with pantoprazole, ranitidine and omeprazole, whereas duodenal ulcer pain was alleviated more rapidly with pantoprazole than ranitidine. Pantoprazole (40mg once daily) showed superior efficacy to famotidine (40mg once daily) in ulcer healing and pain relief after 2 weeks in patients with duodenal ulcer in a large multicentre nonblinded study.

In mild to moderate acute reflux oesophagitis, significantly greater healing was obtained with pantoprazole than with ranitidine and famotidine, whereas similar healing rates were seen with pantoprazole and omeprazole. Pantoprazole showed a significant advantage over ranitidine in relieving symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation. Reflux symptoms were similarly alleviated by pantoprazole and omeprazole.

Preliminary results indicate that triple therapy with pantoprazole, clarithromycin and either metronidazole or imidazole is effective in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori-associated disease; however, these findings require confirmation in large well-controlled studies.

Pantoprazole appears to be well tolerated during short term oral administration, with diarrhoea (1.5%), headache (1.3%), dizziness (0.7%), pruritus (0.5%) and skin rash (0.4%) representing the most frequent adverse events. The drug has lower affinity than omeprazole or lansoprazole for hepatic cytochrome P450 and shows no clinically relevant pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interactions at therapeutic doses with a wide range of drug substrates for this isoenzyme system.

In conclusion, pantoprazole is superior to ranitidine and as effective as omeprazole in the short term treatment of peptic ulcer and reflux oesophagitis, has shown efficacy when combined with antibacterial agents in H. pylori eradication, is apparently well tolerated and offers the potential advantage of minimal risk of drug interaction.

Pharmacodynamic Properties

Pantoprazole causes irreversible inhibition of proton pump (H+, K+-ATPase) function. It is chemically more stable than omeprazole or lansoprazole under neutral to mildly acidic conditions, but is rapidly activated under strongly acidic conditions. This pH-dependent activation profile underlies the improved in vitro selectivity of pantoprazole against parietal H+, K+-ATPase compared with omeprazole.

Oral pantoprazole (20 to 60mg once daily for 5 to 7 days) produces dose-related inhibition of basal, nocturnal and 24-hour gastric acid secretion in healthy volunteers, with minimal additional inhibition at higher doses (80 and 120mg). An intragastric pH >3 was sustained for 8 and 14 hours with pantoprazole 40 and 60mg, respectively, in healthy volunteers. Steady-state gastric acid inhibition was significantly more pronounced when pantoprazole (40mg) was given in the morning rather than the evening. In patients with duodenal ulcer and Helicobacter pylori infection, an intragastric pH >3 was sustained for 19 hours with pantoprazole 40mg.

Oral pantoprazole 40mg appears to be more effective than omeprazole 20mg and as effective as omeprazole 40mg in inhibiting gastric acid secretion in healthy volunteers. Once daily administration of pantoprazole 40mg to healthy volunteers was significantly more effective than omeprazole 20mg in elevating daytime and 24-hour intragastric pH, and marginally more effective than omeprazole 40mg in inhibiting nocturnal acid secretion. Pantoprazole was significantly superior to ranitidine 300mg once daily in increasing median daytime and 24-hour intragastric pH.

Pentagastrin-stimulated acid secretion in healthy volunteers is inhibited in a potent and long-lasting (> 24hours) manner after oral (20 to 40mg once daily) or intravenous (≤80mg single dose; 15 to 30mg once daily) administration of pantoprazole.

In patients with peptic ulcer, a marginally greater elevation in median fasting serum gastrin level was seen after 2 to 4 weeks’ treatment with pantoprazole 40mg once daily (<60%) than with ranitidine 300mg once daily (≈30%), whereas similar increases (≤40%) were seen with pantoprazole 40mg and omeprazole 20mg (both once daily).

Serum pepsinogen I levels are elevated following oral pantoprazole administration, the effect being more exaggerated in patients with H. pylori infection (≤ 150% increase).

Toxicity studies in mice have shown gastric mucosal and submucosal glandular hyperplasia, but no evidence of gastric tumours, on prolonged exposure to high dose pantoprazole. In humans, long term (36 months) therapy with pantoprazole (40 to 80mg daily) has not been associated with any significant increase in enterochromaffin-like cell density.

Pantoprazole does not appear to influence endocrine function on short term administration. No significant changes in adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)-stimulated plasma testosterone or Cortisol levels, or basal plasma thyroid hormone, insulin, glucagon, renin, aldosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteotrophic hormone, prolactin or somatotrophic hormone levels were observed.

Pharmacokinetic Properties

Pantoprazole is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, with peak plasma concentrations of 1.1 to 3.1 mg/L occurring 2 to 4 hours after ingestion of an enteric-coated 40mg tablet. The drug is subject to low first-pass hepatic extraction, displaying an estimated absolute oral bioavailability of 77%. Concomitant food intake does not affect bioavailability. Pantoprazole has a short mean plasma terminal elimination half-life (t1/2β; 0.9 to 1.9 hours); however, inhibition of acid secretion, once accomplished, persists long after the drug has been cleared from the circulation. On repeated oral administration, the pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole (20 and 40 mg once daily) are similar to those after single dose administration.

In accordance with its high degree of plasma protein binding (≈ 98%), Pantoprazole undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P450-mediated oxidation followed by sulphate conjugation. Elimination is predominantly renal, with -80% of an oral or intravenous dose being excreted as urinary metabolites; the remainder is excreted in the faeces and originates primarily from biliary secretion.

The pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole do not appear to be modified to any clinically relevant extent by renal impairment or haemodialysis. Although metabolism and elimination of pantoprazole are impaired in patients with hepatic dysfunction, Cmax is only marginally elevated, indicating that pantoprazole may be administered to patients with hepatic impairment without dosage adjustment. In the elderly, the pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole are comparable to those in the young.

Pantoprazole has lower affinity than omeprazole or lansoprazole for the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system and does not appear to induce CYP activity. In healthy human volunteers, pantoprazole shows no clinically relevant interaction at therapeutic doses with phenazone (antipyrine), diazepam, digoxin, theophylline, carbamazapine, diclofenac, phenprocoumon, phenytoin, warfarin, nifedipine, caffeine, metoprolol or ethanol. In addition, it does not appear to compromise hormonal contraceptive efficacy as no interaction with a low dose combined oral contraceptive was shown. Conversely, the pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole are not modified to any clinically relevant extent by coadministered antacids, phenazone, phenytoin, digoxin or theophylline.

Therapeutic Use

In clinical trials investigating the efficacy of pantoprazole therapy in patients with peptic ulcer or reflux oesophagitis, pantoprazole (40mg), omeprazole (20mg) and famotidine (40mg) were administered once daily, and ranitidine (300mg) was administered as a single daily dose (peptic ulcer) or in 2 divided doses (reflux oesophagitis).

Healing of acute gastric ulcer proceeded significantly faster with pantoprazole than with ranitidine [cumulative ulcer healing rates after 2, 4 and 8 weeks’ treatment of 37, 87 and 97% (pantoprazole) and 19, 58 and 80% (ranitidine)]. However, pain relief was similar with the 2 treatments (72% of pantoprazole and 68% of ranitidine recipients were completely pain-free after 2 weeks).

In comparison with omeprazole, the gastric ulcer healing rate was initially (after 4 weeks) significantly higher with pantoprazole (88 vs 77%); however, after 8 weeks, cumulative ulcer healing rates with the 2 drugs were similar (97 vs 96%). Both drugs rapidly alleviated gastric pain (79% of pantoprazole and 68% of omeprazole recipients were pain-free after 2 weeks), nausea, vomiting, retching, heartburn and acid regurgitation.

Pantoprazole has performed significantly better than ranitidine in healing uncomplicated acute duodenal ulcer and in alleviating ulcer pain. Ulcer healing rates were invariably higher with pantoprazole than with ranitidine (61 to 81% vs 35 to 53% at 2 weeks; 82 to 100% vs 70 to 86% at 4 weeks). This advantage generally translated into a significant superiority for pantoprazole in relief of ulcer pain (77 to 84% vs 58 to 72% of patients pain-free) and other gastrointestinal symptoms (79 to 87 vs 64 to 71 % of patients symptom-free) after 2 weeks’ therapy. pantoprazole has a relatively low apparent volume of distribution (mean 0.16 L/kg at steady-state). Following an initial distribution phase, plasma pantoprazole concentrations decline in a monophasic manner, with an apparent mean t1/2β of 0.9 to 1.9 hours.

Pantoprazole achieved duodenal ulcer healing and pain relief in a significantly larger proportion of patients than did famotidine after 2 weeks (ulcer healing 82 vs 68%; pain relief 87 vs 72%); however, ulcer healing rates were similar in the 2 treatment groups after 4 weeks’ treatment (93 vs 88%).

In contrast, pantoprazole and omeprazole have quantitatively similar effects on duodenal ulcer healing and symptoms. Cumulative ulcer healing rates were similar with the 2 drugs (65 to 74% at 2 weeks; 89 to 96% at 4 weeks), as was relief from ulcer pain (81 to 86% pain-free at 2 weeks).

Recent findings indicate that pantoprazole is effective in the treatment of peptic ulcers poorly responsive to standard or high dosages of histamine H2 receptor antagonists. A healing rate of 96.7% was achieved in patients with ulcers refractory to high dose ranitidine following 2 to 8 weeks’ treatment with pantoprazole 40 to 80 mg/day, and pantoprazole maintenance therapy was effective in preventing ulcer recurrence for up to 3 years.

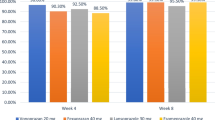

In the treatment of mild to moderate acute reflux oesophagitis, pantoprazole appears to be of equivalent efficacy to standard dose omeprazole but superior to standard dose ranitidine or famotidine. Significantly higher healing rates were obtained with pantoprazole compared to ranitidine (69 vs 57% at 4 weeks; 82 vs 67% at 8 weeks) and famotidine (80 vs 57% at 4 weeks; 93 vs 72% at 8 weeks). Marked symptomatic improvement occurred with pantoprazole and ranitidine as early as week 2 of treatment, with pantoprazole showing a significant advantage in relieving heartburn (weeks 2 and 4) and acid regurgitation (week 4). Overall relief of the 3 main symptoms of reflux (heartburn, acid regurgitation and odynophagia) significantly favoured pantoprazole over ranitidine (72 vs 52% of patients with complete resolution at 4 weeks).

Pantoprazole and omeprazole were equally effective in the endoscopic healing and symptomatic relief of reflux oesophagitis, as reflected in similar ulcer healing rates (74 to 79% vs 75 to 79% at 4 weeks; 90 to 94% vs 91 to 94% at 8 weeks), and rates of resolution of reflux symptoms (59 to 71% vs 69 to 73% at 2 weeks; 83 to 85% vs 80 to 86% at 4 weeks).

One week of triple therapy with pantoprazole (40mg twice daily), clarithromycin (500mg 3 times daily) and metronidazole (500mg 3 times daily) in patients with H. pylori-associated duodenal ulcer achieved an eradication rate of 97% and duodenal ulcer healing in 98% of patients after 4 weeks. Administration of pantoprazole (40mg twice daily), clarithromycin (500mg twice daily) and metronidazole (500mg twice daily) produced H. pylori eradication in all patients with H. pylori associated gastrointestinal disease (n = 25). An eradication rate of 86% was achieved after 5 weeks using 7- to 10-day triple therapy with the same dosage of pantoprazole but lower dosages of clarithromycin (250mg twice daily) and either metronidazole (400mg twice daily) or tinidazole (500mg twice daily).

Tolerability

Pantoprazole has been well tolerated in short term (≤ 8 weeks) and long term studies (up to 4 years) when administered at the standard dosage of 40mg once daily or higher dosages (up to 120 mg/day) to patients with acid-related disorders. On short term administration, the most frequent adverse events with the drug included diarrhoea (1.5%), headache (1.3%), dizziness (0.7%), pruritus (0.5%) and skin rash (0.4%). These were generally of mild or moderate intensity, rarely necessitating treatment withdrawal, and were no more frequent with pantoprazole than with standard dosages of ranitidine and omeprazole. Clinically relevant alterations in routine laboratory parameters have not been noted on short term therapy.

Limited long term (6 months to 4 years) tolerability data in patients with peptic ulcer indicated that pantoprazole was without significant adverse effects, apart from an episode of peripheral oedema which resolved on drug withdrawal, and did not increase enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell density.

Dosage and Administration

Pantoprazole is available as a 40mg enteric-coated tablet for once daily oral administration. Dosage modification is not required in the elderly or in patients with renal or hepatic impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sachs G, Shin JM, et al. The pharmacology of the gastric acid pump: the H+, K+ATPase. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1995; 35: 277–305

Scott DR, Heiander HF, Hersey SJ, et al. The site of acid secretion in the mammalian parietal cell. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993; 1146: 73–80

Shin JM, Besancon M, Simon A, et al. The site of action of pantoprazole in the gastric H+/K+-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993 Jun 5; 1148: 223–33

Shin JM, Besancon M, Prinz C, et al. Continuing development of acid pump inhibitors: site of action of pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994; 8 Suppl. 1: 11–23

Simon WA, Keeling DJ, Laing SM, et al. By 1023/SK & F 96022: biochemistry of a novel (H+, K+)-ATPase inhibitor. Biochem Pharmacol 1990 Jun 1; 39: 1799–806

Figala V, Klemm K, Kohl B, et al. Acid activation of (H+-K+)-ATPase inhibiting 2- (2-pyridylmethyl-sulphinyl)-benzimidazoles: isolation and characterisation of the thiophilic ‘active principle’ and its reactions. J Chem Soc — Chem Commun 1986; 20: 125–7

Beil W, Hannemann H, Mädge S, et al. Inhibition of gastric K+/H+-ATPase by acid activated 2- (2-pyridylmethyl)-sulphinyl) benzimidazole products. Eur J Pharmacol 1987; 133: 37–45

Beil W, Staar U, Sewing K-F. Pantoprazole: a novel H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor with an improved pH stability. Eur J Pharmacol 1992 Aug 6; 218: 265–71

Kohl B, Sturm E, Senn-Bilfinger J, et al. (H+K+)-ATPase inhibiting 2-[(2-pyridylmethyl)sulfinyl]benzimidazoles. 4. A novel series of dimethoxypyridyl-substituted inhibitors with enhanced selectivity. The selection of pantoprazole as a clinical candidate. J Med Chem 1992 Mar 20; 35: 1049–57

Postius S, Bräuer U, Kromer W. The novel proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole elevates intragastric pH for a prolonged period when administered under conditions of stimulated gastric acid secretion in the gastric fistula dog. Life Sci 1991; 49(14): 1047–52

Pedersen PL, Carafoli E. Ion motive ATPases. I. Ubiquity, properties and significance to cell function. Trends Biologi Sci 1987; 12: 146–50

Mauch F, Bode G, Malfertheiner P. Identification and characterization of an ATPase system of Helicobacter pylori and the effect of proton pump inhibitors [letter]. Am J Gastroenterol 1993 Oct; 88: 1801–2

Reill L, Erhardt F, Heinzerling H, et al. Dose-response of pantoprazole 20, 40 and 80 mg on 24-hour intragastric pH, serum pantoprazole and serum gastrin in man [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1994; 106 Suppl.: A 165

Hannan A, Weil J, Broom C, et al. Effects of oral pantoprazole on 24-hour intragastric acidity and plasma gastrin profiles. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1992 Jun; 6: 373–80

Koop H, Kuly S, Flug M, et al. Interactions of intragastric pH and serum gastrin during administration of different doses of the new proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole [abstract]. Dig Dis Sci 1994 Aug; 39: 1780

Brunner G, Luna P, Hartmann M, et al. Pantoprazole I.V. — acid inhibitory treatment for upper GI-bleeding. Gastroenterology. In press

Fried R, Beglinger C, Rose K, et al. Effects of continuous and pH feedback-controlled intravenous pantoprazole on gastric pH in human volunteers [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1995 Apr; 108 Suppl.: A95

Dammann HG, Bethke T, Burkhardt F, et al. Effects of pantoprazole on endocrine function in healthy male volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994 Oct; 8: 549–54

Koop H, Kuly S, Flug M, et al. Comparison of 24-h intragastric pH and 24-h gastrin profiles during therapy with the proton pump inhibitors pantoprazole and omeprazole [abstract]. Gut 1994; 35 Suppl. 4: 79

Reill L, Erhardt F, Fischer R, et al. Effect of oral pantoprazole on 24-hour intragastric pH, serum gastrin profile and drug metabolising enzyme activity in man — a placebo-controlled comparison with ranitidine [abstract]. Gut 1993; 34(4) Suppl.: 63

Scholtz HE, Meyer BH, Luus HG. Comparison of the effects of lansoprazole, omeprazole and pantoprazole on 24-hour gastric pH in healthy males [abstract]. S Afr Med J 1995; 8: 915

Hartmann M, Theiss U, Huber R, et al. 24-hour intragastric pH profiles and pharmacokinetics following single and repeated oral administration of the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole in comparison to omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. In press

Müssig S, Witzel L. Steady-state intragastric pH profile after 40mg pantoprazolexomparison of morning and evening administration [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1993; 104: A154

Savarino V. Farmacologia clinica dei farmaci antisecretori [abstract]. Congresso Nazionale di Gastroenterologia; 1995 Dec 12; Padova, Italy.

Simon B, Müller P, Marinis E, et al. Effect of repeated oral administration of BY 1023/SK & F 96022 — a new substituted benzimidazole derivative — on pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion and pharmacokinetics in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1990 Aug; 4: 373–9

Simon B, Müller P, Hartmann M, et al. Pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion and pharmacokinetics following single and repeated intravenous administration of the gastric H+, K+-ATPase-inhibitor pantoprazole (BY 1023/SK & F96022) in healthy volunteers. Z Gastroenterol 1990 Sep; 28: 443–7

Simon B, Müller P, Bliesath H, et al. Single intravenous admin istration of the H+, K+-ATPase inhibitor BY 1023/SK & F 96022 — inhibition of pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion and pharmacokinetics in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1990 Jun; 4: 239–45

Koop H, Kuly S, Flug M, et al. 24-h Intragastric pH and 24-h gastrin profiles during therapy with different doses of the new proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole [abstract]. Gut 1994; 35 Suppl. 4: 57

Hotz J, Plein K, Schönekäs H. Pantoprazole is superior to ranitidine in the treatment of acute gastric ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995 Feb; 30: 111–5

Schepp W, Classen M. Pantoprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of acute duodenal ulcer. A multicentre study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995; 30: 511–4

Cremer M, Lambert R, Lamers CBH, et al. A double-blind study of pantoprazole and ranitidine in treatment of acute duodenal ulcer. A multicenter trial. Dig Dis Sci 1995; 40: 1360–4

Witzel L, Giitz H, Hüttemann W, et al. Pantoprazole versus omeprazole in the treatment of acute gastric ulcers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995 Feb; 9: 19–24

Beker JA, Bianchi Porro G, Bigard M-A, et al. Double-blind comparison of pantoprazole and omeprazole for the treatment of acute duodenal ulcer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7: 407–10

McColl KEL, El Nujumi AM, Dorrian CA, et al. Helicobacter pylori and hypergastrinaemia during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992 Feb; 27: 93–8

Ten Kate RW, Tuynman HA, Festen HPM, et al. Effect of high dose omeprazole on gastric pepsin secretion and serum pepsinogen levels in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1988; 32: 173–6

Festen HPM, Thys JC, Lamers CB, et al. Effects of oral omeprazole on serum gastrin and serum pepsinogen I levels. Gastroenterology 1984; 87: 1030–4

Larsson H, Carlsson E, Hakanson R, et al. Time-course of development and reversal of gastric endocrine cell hyperplasia after inhibition of acid secretion. Gastroenterology 1988; 95: 1477–86

Havu N. Enterochromaffin-like cell carcinoids of gastric mucosa in rats after life-long inhibition of gastric secretion. Digestion 1986; 35 Suppl. 1: 42–55

Tuch K, Ockert D, Reznik G. Pantoprazole does not induce gastric carcinoids in a 24 month carcinogenicity study in mice [abstract]. Pharmacol Toxicol 1993; 73 Suppl. 2: 75

Brunner G, Harke U. Long-term therapy with pantoprazole in patients with peptic ulceration resistant to extended high-dose ranitidine treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994; 8 Suppl. 1: 59–64

Brunner G, Fischer R, Harke U. Results of long term therapy with pantoprazole in patients with chronic peptic disease [abstract]. Symposium on the precise and effective treatment of acid related diseases — clinical focus on pantoprazole. 1995 May 16; San Diego.

Kromer W, Gönne S, Riedel R, et al. Direct comparison between the ulcer-healing effects of two H+-K+-ATPase inhibitors, one Mselective antimuscarinic and one H2 receptor antagonist in the rat. Pharmacology 1990 Dec; 41: 333–7

Graham DY. Helicobacter: its epidemiology and its role in duodenal ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1991; 6: 105–13

Rauws EAJ, van der Hulst RWM. Current guidelines for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. Drugs 1995; 50: 984–90

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. JAMA 1994; 272: 65–9

Suerbaum S, Leying H, Klemm K, et al. Antibacterial activity of pantoprazole and omeprazole against Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1991 Feb; 10: 92–3

Bardhan KD, Logan RPH, Celestin LR, et al. Clarithromycin (CL) and omeprazole (OM) in the prevention of duodenal ulcer (DU) recurrence and eradication of H. pylori Hp [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 1: 338

O’Morain C, Logan RPH, Clarithromycin European H. Pylori Study Group. Clarithromycin (CL) in combination with omeprazole for healing of duodenal ulcers (DU), prevention of DU recurrence and eradication of H. pylori (HP) in two European studies [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 1: 16

Furuta T, Futami H, Arai H, et al. Effects of lansoprazole with or without amoxicilin on ulcer healing: relation to eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 20 Suppl. 2: S107–11

Parente F, Maconi G, Bargiggia S, et al. Efficacy of amoxycillin compared with classical triple therapy in the eradication of H. pylori after pre-treatment with lansoprazole [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 1: 162

Kenyon CJ, Fraser R, Birnie GG, et al. Dose related in vitro effects of ranitidine and Cimetidine on basal and ACTH-stimulated steroidogenesis. Gut 1986; 27: 1143–5

Pont A, Williams PL, Loose DS, et al. Ketoconazole blocks adrenal steroid synthesis. Ann Intern Med 1982; 97: 370–2

Dowie LJ, Smith JE, MacGilchrist AJ, et al. In vivo and in vitro studies on the site of inhibitory action of omeprazole on adrenocortical steroidogenesis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1988; 35: 625–9

Bliesath H, Hartmann M, Huber R, et al. Lack of influence of pantoprazole on cardiovascular function in healthy volunteers: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled crossover study. Clin Drug Invest 1995 Feb; 9: 72–8

Herberg K-W, Bliesath H, Neukirchen B, et al. The proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole does not impair safety related performance [abstract]. Gut 1994; 35 Suppl. 4: 73

Huber R, Muller W, Banks MC, et al. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of the H+/K+ ATPase inhibitor (BY 1023/SK & F 96,022) and its sulphone metabolite in serum or plasma by direct injection and fully automated pre-column sample clean-up. J Chromatogr 1990 Aug 3; 529: 389–401

Doyle E, McDowall RD, Murkitt GS, et al. Two systems for the automated analysis of drugs in biological fluids using high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr 1990 Apr 27; 527: 67–77

Bliesath H, Huber R, Hartmann M, et al. Dose linearity of the pharmacokinetics of the new H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor pantoprazole after single intravenous administration. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994 Jan; 32: 44–50

Breuel HP, Hartmann M, Bondy S, et al. Pantoprazole in the elderly: no dose-adjustment [abstract]. Gut 1994; 35 Suppl. 4: 77

Pue MA, Laroche J, Meineke I, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole following single intravenous and oral administration to healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 44(6): 575–8

Huber R, Kohl B, Sachs G, et al. The continuing development of proton pump inhibitors, with particular reference to pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995; 9: 363–78

Tucker GT. The interaction of proton pump inhibitors with cytochromes P450. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994; 8 Suppl. 1: 33–8

Peeters PAM, Oosterhuis B, Zech K, et al. Pantoprazole pharmacokinetics and metabolism after oral and intravenous administration of 14C-labelled pantoprazole to young healthy male volunteers [abstract]. Pharm World Sci 1993 Dec 17; 15 Suppl. L: L7

Lins RL, de Clercq I, Hartmann M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole in patients with severe renal impairment [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1994; 106: 126

Benet LZ, Zech K. Pharmacokinetics — a relevant factor for the choice of a drug? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994; 8 Suppl. 1: 25–32

Kliem V, Hartmann M, Huber R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole in hemodialysis patients [abstract]. Kidney Int 1995 Mar; 47: 984

Brunner G, Chang J, Hartmann M, et al. Pharmakokinetik von Pantoprazol bei Patienten mit Leberzirrhose. Med Klin 1994; 89 Suppl. 1: 189

Dickins M, Bridges JW. The relationship between the binding of 2-n-alkylbenzimidazoles to rat hepatic microsomal cytochrome P-450 and the inhibition of monooxygenation. Biochem Pharmacol 1982; 31: 1315–20

Simon WA, Büdingen C, Fahr S, et al. The H+, K+-ATPase inhibitor pantoprazole (BY1023/SK-&- F96022) interacts less with cytochrome-P450 than omeprazole and lansoprazole. Biochem Pharmacol 1991 Jul 5; 42: 347–55

Hanauer G, Graf U, Meissner T. In vivo cytochrome P 450 interactions of the newly developed H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor pantoprazole (BY 1023/SK & F 96022) compared to other antiulcer drugs. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1991 Jan-Feb; 13: 63–7

Kromer W, Postius S, Riedel R, et al. BY 1023/SK & F 96022 INN pantoprazole, a novel gastric proton pump inhibitor, potently inhibits acid secretion but lacks relevant cytochrome P450 interactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990 Jul; 254: 129–35

Heinemeyer G, Roots I, Lestau L, et al. d-Glutaric acid excretion in critical care patients — comparison with 6β-hydroxycortisol excretion and serum γ-glutamyltranspeptidase activity and relation to multiple drug therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 21: 9–18

Hartmann M, Bliesath H, Zech K, et al. Lack of induction of CYP1A2 activity in man by pantoprazole [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 2: 363

Andersson T. Omeprazole drug interaction studies. Clin Pharmacokinet 1991; 21: 195–212

Greene W. Drug interactions involving Cimetidine — mechanisms, documentation, implications. Drug Metabol Drug Interact 1984; 5: 25–51

Steinijans VW, Huber R, Hartmann M, et al. Lack of pantoprazole drug interactions in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994 Aug; 32: 385–99

De Mey C, Meineke I, Steinijans VW, et al. Pantoprazole lacks interaction with antipyrine in man, either by inhibition or induction. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1994; 32: 98–106

Gugler R, Hartmann M, Rudi J, et al. Lack of interaction of pantoprazole and diazepam in man [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1992 Apr; 102: A77

Hartmann M, Huber R, Bliesath H, et al. Lack of interaction between pantoprazole and digoxin at therapeutic doses in man. In: Management of acid-related diseases: Focus on pantoprazole. Congress Abstracts, Charité, Berlin, 1993; 34-35

Hartmann M, Huber R, Bliesath H, et al. Lack of interaction between pantoprazole and digoxin at therapeutic doses in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995; 33: 481–5

Schulz H-U, Hartmann M, Steinijans VW, et al. Lack of influence of pantoprazole on the disposition kinetics of theophylline in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1991 Sep; 29: 369–75

Huber R, Bliesath H, Hartmann M, et al. Pantoprazole does not interact with the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine. Gastroenterology. In press

Bliesath H, Huber R, Hartmann M, et al. Pantoprazole lacks interaction with diclofenac in man [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 2: 368

Ehrlich A, Fuder H, Hartmann M, et al. Pantoprazole lacks pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interaction with phenprocoumon in man [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 2: 1133

Middle MV, Müller FO, Schall R, et al. No influence of pantoprazole on the pharmacokinetcs of phenytoin. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995 May; 33: 304–7

Duursema L, Müller FO, Schall R, et al. Lack of effect of pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 39: 700–3

Bliesath H, Huber R, Hartmann M, et al. Pantoprazole does not influence the steady state pharmacokinetics of nifedipine [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1994 Apr; 106 Suppl.: 55

Koch HJ, Hartmann M, Bliesath H, et al. Pantoprazole does not influence metoprolol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in man. Gastroenterology. In press

Teyssen S, Singer MV, Heinze H, et al. Pantoprazole does not influence the pharmacokinetics of ethanol in healthy volunteers. Gastroenterology. In press

Middle MV, Müller FO, Schall R, et al. Effect of pantoprazole on ovulation suppression by a low-dose hormonal contraceptive. Clin Drug Invest 1995 Jan; 9: 54–6

Hartmann M, Bliesath H, Huber R, et al. Lack of influence of antacids on the pharmacokinetics of the new gastric H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor pantoprazole [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1994 Apr; 106 Suppl.: A91

Baccaro JC, Besasso H, Dávolos JR, et al. Pantoprazole is superior to ranitidine in the treatment of florid duodenal ulcer. Preliminary results of a pantoprazole multicenter study in Argentina. Gastroenterology. In press

Castro LP, Lyra LGC, Malafaia O, et al. Pantoprazole achieves better healing than ranitidine in the treatment of acute duodenal ulcer. Pantoprazole multicenter study in Brazil. Gastroenterology. In press

Dibildox M, Tomás-Pons J, Rose K, et al. Clinical superiority of pantoprazole over ranitidine in the treatment of patients with florid duodenal ulcers. Mexican multicentre study [abstract]. Gut 1995; 37 Suppl. 2: 186

Judmaier G, Koelz HR, Pantoprazole-Duodenal Ulcer-SG. Comparison of pantoprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of acute duodenal ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994 Feb; 8: 81–6

van Rensburg CJ, van Eeden PJ, Marks IN, et al. Improved duodenal ulcer healing with pantoprazole compared with ranitidine: a multicentre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1994; 6: 739–43

Rehner M, Rohner HG, Schepp W. Comparison of pantoprazole versus omeprazole in the treatment of acute duodenal ulceration — a multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995; 9: 411–6

Koop H, Schepp W, Dammann HG, et al. Comparative trial of pantoprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of reflux esophagitis: results of a German multicenter study. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995 Apr; 20: 192–5

Belaiche J, Colin R, Corinaldesi R, et al. Efficacy of pantoprazole compared to omeprazole in reflux esophagitis — European Multicenter Study. 10th World Congress of Gastroenterology 1994 Abstracts II, abstr. 2556P, 1994.

Hotz J, Gangl A, Heinzerling H. Pantoprazole vs. omeprazole in acute reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. In press

Mössner J, Hölscher AH, Herz R, et al. A double-blind study of pantoprazole and omeprazole in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis: a multicentre trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995; 9: 321.–6

Müller P, Simon B, Khalil H, et al. Dose-range finding study with the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole in acute duodenal ulcer patients. Z Gastroenterol 1992 Nov; 30: 771–5

Rohner HG, Dietrich K, Rosprich G, et al. One year follow-up in duodenal ulcer patients with pantoprazole or ranitidine. 10th World Congress of Gastroenterology 1994; Abstracts II: abstr. 35P

Hahn EG, Dammann HG, Adler G, et al. Pantoprazole provides faster healing and pain relief than famotidine in acute duodenal ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. In press

Bardhan KD, Cherian P, Polak JM, et al. Pantoprazole (PANTO) in aggressive or refractory acid-peptic disease. Gastroenterology. In press

von Kleist D-H, Bosseckert H, Scholten T, et al. Pantoprazole versus ranitidine in acid-related disease: results of the German pantoprazole phase IV program. Gastroenterology. In press

Dammann HG, Hahn EG, Adler G, et al. Pantoprazole is more effective than famotidine in acute gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. In press

Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. Cure of duodenal ulcer associated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 1990; 1: 1233–5

Markham A, McTavish D. Clarithromycin and omeprazole as Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with H. pylori-associated gastric disorders. Drugs 1996; 51: 161–78

Bazzoli F, Zagari RM, Fossi S, et al. Short-term low-dose triple therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1994; 6: 773–7

Goddard A, Logan R. One-week low-dose triple therapy: new standards for Helicobacter pylori treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7: 1–3

Adamek RJ, Bethke T, International Pantoprazole Hp-Study Group. Pantoprazole, clarithromycin and metronidazole vs pantoprazole and clarithromycin for cure of H. pylori infection in duodenal ulcer patients. Gastroenterology. In press

Adamek RJ, Szymanski C, Pfaffenbach B, et al. Short-term triple treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection with pantoprazole, clarithromycin and metronidazole [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1995 Mar 17; 120: 358–60

Labenz J, Peitz U, Tillenburg B, et al. Short-term triple therapy with pantoprazole, clarithromycin and metronidazole to eradicate Helicobacter pylori. Leber Magen Darm 1995; 25: 122–7

Bardhan KD. Short term triple therapy for cure of H. pylori infection [abstract]. Satellite symposium on therapy of acid-related diseases — expectations in the era of PPIs. 1995 Sep 16; Berlin

Brunner G, Schneider A, Harke U. Long-term therapy with pantoprazole in patients with H2-bIocker refractory acid-peptic disease [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1994 Apr; 106 Suppl.: 57

Brunner G, Harke U, Schneider A, et al. Long-term management of H2-blocker refractory acid-peptic disease with pantoprazole. Gastroenterology. In press

Pantoprazole: product monograph. Byk Gulden, Konstanz, Germany. (Data on file)

Scholten T, Adler G, Bosseckert H, et al. Clinical tolerability of pantoprazole compared to H2-antagonists: results of the German pantoprazole phase IV program. Gastroenterology. In press

Brunner G, Thiesemann C, Ratz H. High plasma concentrations of proton pump inhibitors cause peripheral oedema in female patients. Gastroenterology 1993 Apr; 104 Suppl.: A48

Berstad A, Hatlebakk JG. Lansoprazole in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis: a survey of clinical studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1993; 7 Suppl. 1: 34–6

Wilde MI, McTavish D. Omeprazole. An update of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in acid-related disorders. Drugs 1994; 48: 91–132

Jones DB, Howden CW, Burget DW, et al. Acid suppression in duodenal ulcer: a meta-analysis to define optimal dosing with antisecretory drugs. Gut 1987; 28: 1120–7

Bardhan KD. Is there any acid peptic disease that is refractory to proton pump inhibitors? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1993; 7 Suppl. 1: 13–24

Deakin M, Williams JG. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists in peptic ulcer disease: efficacy in healing peptic ulcers. Drugs 1992; 44: 709–19

Forbes GM, Glaser ME, Cullen DJ, et al. Duodenal ulcer treated with Helicobacter pylori eradication. Seven year follow-up. Lancet 1994; 1: 258–60

Marshall BJ, Goodwin CS, Warren JR. Prospective double-blind trial of duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Campylobacter pylori. Lancet 1989; 2: 1437–41

Savarino V, Vigneri S. How should we decide on the best regimen for eradicating Helicobacter pylori? BMJ 1995; 311: 581–2

Andersson T, Andrén K, Cederberg C, et al. Effect of omeprazole and Cimetidine on plasma diazepam levels. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1990; 39: 51–4

Naidu MUR, Shobha JC, Dixit VK, et al. Effect of multiple dose omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine. Drug Invest 1994; 7: 8–12

Gugler R, Jensen JC. Omeprazole inhibits oxidative drug metabolism — studies with diazepam and phenytoin in vivo and 7-ethoxycoumarin in vitro. Gastroenterology 1985; 89: 1235–41

Sutfin T, Balmer K, Boström H, et al. Stereoselective interaction of omeprazole with warfarin in healthy men. Ther Drug Monit 1989; 11: 176–84

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Various sections of the manuscript reviewed by: G. Brunner, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Abt für Gastroenterologie und Hepatologie, Hannover, Germany; G. Dobrilla, Divisione di Gastroenterologia, Ospedale Generale Regionale, Bolzano, Italy; C. Howden, Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition, The University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina, USA; G. Judmaier, Clinic of Internal Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Innsbruck, Austria; U. Klotz, Dr. Margarete Fischer-Bosch-Institut für Klinische Pharmakologie, Stuttgart, Germany; H. Koop, 4th Department of Medicine, Klinikum Buch, Berlin, Germany; T. Miwa, Department of Internal Medicine, Tokai University School of Medicine, Kanagawa, Japan; J. Mössner, Zentrum für Innere Medizin, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik II, Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany; F.O. Müller, FARMOVS Institute for Clinical Pharmacology and Drug Development, Department of Pharmacology, University of the Orange Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa; G. Sachs, Department of Physiology and Medicine, Wadsworth VAMC and ACLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA; B. Simon, Facharzt für Innere Medizin-Gastroenterologie, Krankenhaus Schwetzingen, Schwetzingen, Germany; C.J. van Rensburg, Gastroenterology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Tygerberg Hospital, Tygerberg, South Africa.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03259131.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitton, A., Wiseman, L. Pantoprazole. Drugs 51, 460–482 (1996). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199651030-00012

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199651030-00012